The Russian language belongs to the Finn-Ugric family. Finno-Ugric family of languages. Common structural features and common vocabulary

Peoples

About the Ural peoples

The history of the Uralic languages and peoples goes back many millennia. The process of formation of modern Finnish, Ugric and Samoyed peoples was very complex. The former name of the Uralic family of languages - Finno-Ugric, or Finno-Ugric family, was later replaced by Uralic, since the Samoyed languages belonged to this family was discovered and proven.

The Uralic language family is divided into the Ugric branch, which includes the Hungarian, Khanty and Mansi languages (the latter two are united under the general name "Ob-Ugric languages"), into the Finno-Permian branch, which unites the Perm languages (Komi, Komi- Permyak and Udmurt), Volga languages (Mari and Mordovian), the Baltic-Finnish language group (Karelian, Finnish, Estonian languages, as well as the languages of the Vepsians, Vodi, Izhora, Livs), Sami and Samoyed languages, within which the northern branch (Nganasan) is distinguished , Nenets, Enets languages) and the southern branch (Selkup).

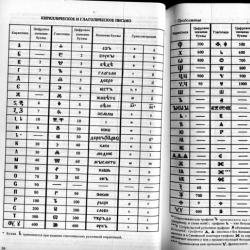

Writing for Karelians (in two dialects - Livvik and Karelian proper) and Vepsians was restored on a Latin basis in 1989. The rest of the peoples of Russia use a writing system based on the Cyrillic alphabet. Hungarians, Finns and Estonians living in Russia use the Latin-based script adopted in Hungary, Finland and Estonia.

The Uralic languages are very diverse and differ markedly from each other.

In all languages united in the Uralic language family, a common lexical layer has been identified, which allows us to assert that 6-7 thousand years ago there was a more or less unified proto-language (base language), which suggests the presence of a proto-Uralic community speaking this language.

The number of peoples speaking Uralic languages is about 23 - 24 million people. The Ural peoples occupy a vast territory that stretches from Scandinavia to the Taimyr Peninsula, with the exception of the Hungarians, who, by the will of fate, found themselves apart from the other Ural peoples - in the Carpathian-Danube region.

Most of the Ural peoples live in Russia, with the exception of Hungarians, Finns and Estonians. The most numerous are the Hungarians (more than 15 million people). The second largest people are the Finns (about 5 million people). There are about a million Estonians. On the territory of Russia (according to the 2002 census) live Mordovians (843,350 people), Udmurts (636,906 people), Mari (604,298 people), Komi-Zyryans (293,406 people), Komi-Permyaks (125,235 people), Karelians (93,344 people) , Vepsians (8240 people), Khanty (28678 people), Mansi (11432 people), Izhora (327 people), Vod (73 people), as well as Finns, Hungarians, Estonians, Sami. Currently, the Mordovians, Mari, Udmurts, Komi-Zyrians, and Karelians have their own national-state entities, which are republics within the Russian Federation.

Komi-Permyaks live on the territory of the Komi-Permyak Okrug of the Perm Territory, the Khanty and Mansi - the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug-Ugra of the Tyumen Region. Vepsians live in Karelia, in the northeast of the Leningrad region and in the northwestern part of the Vologda region, the Sami live in the Murmansk region, in the city of St. Petersburg, the Arkhangelsk region and Karelia, the Izhora live in the Leningrad region, the city of St. Petersburg, the Republic of Karelia . Vod - in the Leningrad region, in the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Finno-Ugric languages

Finno-Ugric languages are a group of languages that go back to a single Finno-Ugric proto-language. They form one of the branches of the Uralic family of languages, which also includes the Samoyedic languages. Finno-Ugric languages according to the degree of relationship are divided into groups: Baltic-Finnish (Finnish, Izhorian, Karelian, Vepsian, Votic, Estonian, Livonian), Sami (Sami), Volga (Mordovian - Moksha and Erzyan languages, Mari), Permian (Komi -Zyrian, Komi-Permyak, Udmurt), Ugric (Hungarian, Khanty, Mansi). Speakers of the Finno-Ugric language live in northeastern Europe, in part of the Volga-Kama region and the Danube basin, in Western Siberia.

The number of speakers of Finno-Ugric languages is currently about 24 million people, including Hungarians - 14 million, Finns - 5 million, Estonians - 1 million. According to the 1989 census, 1,153 people live in Russia 987 Mordvins, 746,793 Udmurts, 670,868 Mari, 344,519 Komi-Zyryans, 152,060 Komi-Permyaks, 130,929 Karelians, as well as 1,890 Sami, 22,521 Khanty and 8,474 Mansi. Hungarians (171,420 people) and Finns (67,359 people) also live in Russia.

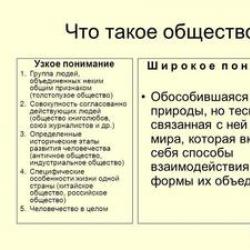

In traditional Finno-Ugric studies, the following diagram of the family tree of the Finno-Ugric languages, proposed by the Finnish scientist E. Setälä, is accepted (see figure).

According to chronicles, there were also Finno-Ugric languages Merya and Muroma, which fell out of use in the Middle Ages. It is possible that in ancient times the composition of Finno-Ugric languages was wider. This is evidenced, in particular, by numerous substratum elements in Russian dialects, toponymy, and the language of folklore. In modern Finno-Ugric studies, the Meryan language, which represented an intermediate link between the Baltic-Finnish and Mordovian languages, has been fairly fully reconstructed.

Few Finno-Ugric languages have long written traditions. Thus, the most ancient written monuments belong to the Hungarian language (12th century), later Karelian texts (13th century) and monuments of ancient Komi writing (14th century) appeared. The Finnish and Estonian languages received writing in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Udmurt and Mari languages - in the 18th century. Some Baltic-Finnish languages remain unwritten to this day.

According to most scientists, the Proto-Finno-Ugric and Proto-Samoedic branches separated from the Uralic proto-language in the 6-4 millennium BC. Then separate Finno-Ugric languages developed. In the course of their history, they were influenced by neighboring unrelated Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Indo-Iranian and Turkic languages, and began to differ significantly from each other. The history of the Sami language is interesting in this regard. There is a hypothesis that the Sami group arose as a result of the transition of the aboriginal population of the Far North of Europe to the use of one of the Finno-Ugric languages, close to the Baltic-Finnish languages.

The degree of similarity between the individual Finno-Ugric languages that make up the linguistic branches is not the same. Thus, researchers note the great similarity of the Hungarian and Mansi languages, the relative proximity of the Perm and Hungarian languages. Many Finno-Ugric scholars doubt the existence of a single ancient Volga language group and the Volga-Finnish proto-language and consider the Mari and Mordovian languages to be representatives of separate language groups.

Finno-Ugric languages are still characterized by common properties and patterns. Many modern people are characterized by vowel harmony, fixed word stress, the absence of voiced consonants and combinations of consonants at the beginning of words, and regular interlingual phonetic correspondences. Finno-Ugric languages are united by an agglutinative structure with varying degrees of severity. They are characterized by the absence of grammatical gender, the use of postpositions, the presence of a personal-possessive declension, the expression of negation in the form of a special auxiliary verb, the richness of impersonal forms of the verb, the use of a determiner before the qualifier, the invariability of the numeral and adjective in the function of the determiner. In modern Finno-Ugric languages, at least 1000 common Proto-Finno-Ugric roots have been preserved. A number of features bring them closer to languages of other families - Altaic and Indo-European. Some scientists also believe that the Yukaghir language, which is part of the group of Paleo-Asian languages, is close to the Finno-Ugric (Uralic) languages.

Currently, small Finno-Ugric languages are threatened with extinction. These are Votic, Livonian and Izhorian languages, the speakers of which are very few. Population censuses indicate a reduction in the number of Karelians, Mordovians, and Vepsians; The number of speakers of Udmurt, Komi and Mari languages is decreasing. For several decades, the scope of use of Finno-Ugric languages has been declining. Only recently has the public paid attention to the problem of their preservation and development.

Sources:

- Historical and cultural atlas of the Komi Republic. - M., 1997.

- Finno-Ugric and Samoyed peoples: Statistical collection. - Syktyvkar, 2006.

- Tsypanov E.A. "Encyclopedia. Komi language". - Moscow, 1998. - pp. 518-519

Looking at the geographical map of Russia, you can see that in the basins of the Middle Volga and Kama river names ending in “va” and “ha” are common: Sosva, Izva, Kokshaga, Vetluga, etc. Finno-Ugrians live in those places, and translated from their languages "va" And "ha" mean "river", "moisture", "wet place", "water". However, Finno-Ugric toponyms{1 ) are found not only where these peoples make up a significant part of the population, form republics and national districts. Their distribution area is much wider: it covers the European north of Russia and part of the central regions. There are many examples: the ancient Russian cities of Kostroma and Murom; the Yakhroma and Iksha rivers in the Moscow region; Verkola village in Arkhangelsk, etc.

Some researchers consider even such familiar words as “Moscow” and “Ryazan” to be Finno-Ugric in origin. Scientists believe that Finno-Ugric tribes once lived in these places, and now the memory of them is preserved by ancient names.

{1 } Toponym (from the Greek “topos” - “place” and “onima” - “name”) is a geographical name.

WHO ARE THE FINNO-UGRICS

Finns called people inhabiting Finland, neighboring Russia(in Finnish " Suomi "), A Ugrians in ancient Russian chronicles they were called Hungarians. But in Russia there are no Hungarians and very few Finns, but there are peoples speaking languages related to Finnish or Hungarian . These peoples are called Finno-Ugric . Depending on the degree of similarity of languages, scientists divide Finno-Ugric peoples into five subgroups . Firstly, Baltic-Finnish , included Finns, Izhorians, Vodians, Vepsians, Karelians, Estonians and Livonians. The two most numerous peoples of this subgroup are Finns and Estonians- live mainly outside our country. In Russia Finns can be found in Karelia, Leningrad region and St. Petersburg;Estonians - V Siberia, Volga region and Leningrad region. A small group of Estonians - setu - lives in Pechora district of Pskov region. By religion, many Finns and Estonians - Protestants (usually, Lutherans), setu - Orthodox . Little people Vepsians lives in small groups in Karelia, Leningrad region and in the north-west of Vologda, A water (there are less than 100 people left!) - in Leningradskaya. AND Veps and Vod - Orthodox . Orthodoxy is professed and Izhorians . There are 449 of them in Russia (in the Leningrad region), and about the same number in Estonia. Vepsians and Izhorians have preserved their languages (they even have dialects) and use them in everyday communication. The Votic language has disappeared.

The biggest Baltic-Finnish people of Russia - Karelians . They live in Republic of Karelia, as well as in the Tver, Leningrad, Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions. In everyday life, Karelians speak three dialects: Karelian, Lyudikovsky and Livvikovsky, and their literary language is Finnish. Newspapers and magazines are published there, and the Department of Finnish Language and Literature operates at the Faculty of Philology of Petrozavodsk University. Karelians also speak Russian.

The second subgroup consists Sami , or Lapps . Most of them are settled in Northern Scandinavia, but in Russia Sami- inhabitants Kola Peninsula. According to most experts, the ancestors of this people once occupied a much larger territory, but over time they were pushed to the north. Then they lost their language and adopted one of the Finnish dialects. The Sami are good reindeer herders (in the recent past they were nomads), fishermen and hunters. In Russia they profess Orthodoxy .

In the third, Volga-Finnish , subgroup includes Mari and Mordovians . Mordva- indigenous population Republic of Mordovia, but a significant part of this people live throughout Russia - in Samara, Penza, Nizhny Novgorod, Saratov, Ulyanovsk regions, in the republics of Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, in Chuvashia etc. Even before the annexation in the 16th century. Mordovian lands to Russia, the Mordovians had their own nobility - "inyazory", "otsyazory"", i.e. "owners of the land." Inyazory They were the first to be baptized, quickly became Russified, and later their descendants formed an element in the Russian nobility that was slightly smaller than those from the Golden Horde and the Kazan Khanate. Mordva is divided into Erzya and Moksha ; each of the ethnographic groups has a written literary language - Erzya and Moksha . By religion Mordovians Orthodox ; they have always been considered the most Christianized people of the Volga region.

Mari live mainly in Republic of Mari El, as well as in Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, Udmurtia, Nizhny Novgorod, Kirov, Sverdlovsk and Perm regions. It is generally accepted that this people has two literary languages - Meadow-Eastern and Mountain Mari. However, not all philologists share this opinion.

Even ethnographers of the 19th century. noted the unusually high level of national self-awareness of the Mari. They stubbornly resisted joining Russia and baptism, and until 1917 the authorities forbade them to live in cities and engage in crafts and trade.

In the fourth, Permian , the subgroup itself includes Komi , Komi-Permyaks and Udmurts .Komi(in the past they were called Zyryans) form the indigenous population of the Komi Republic, but also live in Sverdlovsk, Murmansk, Omsk regions, in the Nenets, Yamalo-Nenets and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrugs. Their original occupations are farming and hunting. But, unlike most other Finno-Ugric peoples, there have long been many merchants and entrepreneurs among them. Even before October 1917 Komi in terms of literacy (in Russian) approached the most educated peoples of Russia - Russian Germans and Jews. Today, 16.7% of Komi work in agriculture, but 44.5% work in industry, and 15% work in education, science, and culture. Part of the Komi - the Izhemtsy - mastered reindeer husbandry and became the largest reindeer herders in the European north. Komi Orthodox (partly Old Believers).

Very close in language to the Zyryans Komi-Permyaks . More than half of this people live in Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug, and the rest - in the Perm region. Permians are mainly peasants and hunters, but throughout their history they were also factory serfs in the Ural factories, and barge haulers on the Kama and Volga. By religion Komi-Permyaks Orthodox .

Udmurts{ 2 } concentrated mostly in Udmurt Republic, where they make up about 1/3 of the population. Small groups of Udmurts live in Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, the Republic of Mari El, in the Perm, Kirov, Tyumen, Sverdlovsk regions. The traditional occupation is agriculture. In cities, they most often forget their native language and customs. Perhaps this is why only 70% of Udmurts, mostly residents of rural areas, consider the Udmurt language as their native language. Udmurts Orthodox , but many of them (including the baptized) adhere to traditional beliefs - they worship pagan gods, deities, and spirits.

In the fifth, Ugric , subgroup includes Hungarians, Khanty and Mansi . "Ugrimi "in Russian chronicles they called Hungarians, A " Ugra " - Ob Ugrians, i.e. Khanty and Mansi. Although Northern Urals and lower reaches of the Ob, where the Khanty and Mansi live, are located thousands of kilometers from the Danube, on the banks of which the Hungarians created their state; these peoples are their closest relatives. Khanty and Mansi belong to the small peoples of the North. Muncie live mainly in X Anti-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, A Khanty - V Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrugs, Tomsk Region. The Mansi are primarily hunters, then fishermen and reindeer herders. The Khanty, on the contrary, are first fishermen, and then hunters and reindeer herders. Both of them confess Orthodoxy, however, they did not forget the ancient faith. The industrial development of their region caused great damage to the traditional culture of the Ob Ugrians: many hunting grounds disappeared and the rivers became polluted.

Old Russian chronicles preserved the names of Finno-Ugric tribes that have now disappeared - Chud, Merya, Muroma . Merya in the 1st millennium AD e. lived in the area between the Volga and Oka rivers, and at the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennia merged with the Eastern Slavs. There is an assumption that modern Mari are descendants of this tribe. Murom in the 1st millennium BC. e. lived in the Oka basin, and by the 12th century. n. e. mixed with the Eastern Slavs. Chudyu modern researchers consider the Finnish tribes that lived in ancient times along the banks of the Onega and Northern Dvina. It is possible that they are the ancestors of the Estonians.

{ 2 )Russian historian of the 18th century. V.N. Tatishchev wrote that the Udmurts (formerly called Votyaks) perform their prayers “beside any good tree, but not near pine and spruce, which have no leaves or fruit, but aspen is revered as a cursed tree... ".

WHERE THE FINNO-UGRICS LIVED AND WHERE THE FINNO-UGRIANS LIVE

Most researchers agree that the ancestral home Finno-Ugrians

was on the border of Europe and Asia, in the areas between the Volga and Kama and in the Urals. It was there in the IV-III millennia BC. e. A community of tribes arose, related in language and similar in origin. By the 1st millennium AD. e. the ancient Finno-Ugrians settled as far as the Baltic states and Northern Scandinavia. They occupied a vast territory covered with forests - almost the entire northern part of what is now European Russia to the Kama River in the south.

Most researchers agree that the ancestral home Finno-Ugrians

was on the border of Europe and Asia, in the areas between the Volga and Kama and in the Urals. It was there in the IV-III millennia BC. e. A community of tribes arose, related in language and similar in origin. By the 1st millennium AD. e. the ancient Finno-Ugrians settled as far as the Baltic states and Northern Scandinavia. They occupied a vast territory covered with forests - almost the entire northern part of what is now European Russia to the Kama River in the south.

Excavations show that the ancient Finno-Ugrians belonged to Ural race: their appearance is a mixture of Caucasian and Mongoloid features (wide cheekbones, often Mongolian eye shape). Moving west, they mixed with Caucasians. As a result, among some peoples descended from the ancient Finno-Ugrians, Mongoloid features began to smooth out and disappear. Nowadays, “Ural” features are characteristic to one degree or another of everyone to the Finnish peoples of Russia: average height, wide face, nose, called “snub”, very light hair, sparse beard. But in different peoples these features manifest themselves in different ways. For example,  Mordovian-Erzya tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed, and Mordovian-Moksha and shorter in stature, with a wider face, and their hair is darker. U Mari and Udmurts Often there are eyes with the so-called Mongolian fold - epicanthus, very wide cheekbones, and a thin beard. But at the same time (the Ural race!) has blond and red hair, blue and gray eyes. The Mongolian fold is sometimes found among Estonians, Vodians, Izhorians, and Karelians. Komi they are different: in those places where there are mixed marriages with the Nenets, they have black hair and braids; others are more Scandinavian-like, with a slightly wider face.

Mordovian-Erzya tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed, and Mordovian-Moksha and shorter in stature, with a wider face, and their hair is darker. U Mari and Udmurts Often there are eyes with the so-called Mongolian fold - epicanthus, very wide cheekbones, and a thin beard. But at the same time (the Ural race!) has blond and red hair, blue and gray eyes. The Mongolian fold is sometimes found among Estonians, Vodians, Izhorians, and Karelians. Komi they are different: in those places where there are mixed marriages with the Nenets, they have black hair and braids; others are more Scandinavian-like, with a slightly wider face.

Finno-Ugrians were engaged in agriculture (in order to fertilize the soil with ash, they burned areas of the forest), hunting and fishing . Their settlements were far from each other. Perhaps for this reason they did not create states anywhere and began to be part of neighboring organized and constantly expanding powers. Some of the first mentions of the Finno-Ugrians contain Khazar documents written in Hebrew, the state language of the Khazar Kaganate. Alas, there are almost no vowels in it, so one can only guess that “tsrms” means “Cheremis-Mari”, and “mkshkh” means “moksha”. Later, the Finno-Ugrians also paid tribute to the Bulgars and were part of the Kazan Khanate and the Russian state.

RUSSIANS AND FINNO-UGRICS

In the XVI-XVIII centuries. Russian settlers rushed to the lands of the Finno-Ugric peoples. Most often, settlement was peaceful, but sometimes indigenous peoples resisted the entry of their region into the Russian state. The Mari showed the most fierce resistance.

Over time, baptism, writing, and urban culture brought by the Russians began to displace local languages and beliefs. Many began to feel like Russians - and actually became them. Sometimes it was enough to be baptized for this. The peasants of one Mordovian village wrote in a petition: “Our ancestors, the former Mordovians,” sincerely believing that only their ancestors, pagans, were Mordovians, and their Orthodox descendants are in no way related to the Mordovians.

People moved to cities, went far away - to Siberia, to Altai, where everyone had one language in common - Russian. The names after baptism were no different from ordinary Russian ones. Or almost nothing: not everyone notices that there is nothing Slavic in surnames like Shukshin, Vedenyapin, Piyasheva, but they go back to the name of the Shuksha tribe, the name of the goddess of war Veden Ala, the pre-Christian name Piyash. Thus, a significant part of the Finno-Ugrians was assimilated by the Russians, and some, having converted to Islam, mixed with the Turks. That is why the Finno-Ugric people do not constitute a majority anywhere - even in the republics to which they gave their name.

But, having disappeared into the mass of Russians, the Finno-Ugrians retained their anthropological type: very blond hair, blue eyes, a “bubble” nose, and a wide, high-cheekboned face. The type that writers of the 19th century. called the “Penza peasant”, is now perceived as typically Russian.

Many Finno-Ugric words have entered the Russian language: “tundra”, “sprat”, “herring”, etc. Is there a more Russian and beloved dish than dumplings? Meanwhile, this word is borrowed from the Komi language and means “bread ear”: “pel” is “ear”, and “nyan” is “bread”. There are especially many borrowings in northern dialects, mainly among the names of natural phenomena or landscape elements. They add a unique beauty to local speech and regional literature. Take, for example, the word “taibola”, which in the Arkhangelsk region is used to call a dense forest, and in the Mezen River basin - a road running along the seashore next to the taiga. It is taken from the Karelian "taibale" - "isthmus". For centuries, peoples living nearby have always enriched each other's language and culture.

Patriarch Nikon and Archpriest Avvakum were Finno-Ugrians by origin - both Mordvins, but irreconcilable enemies; Udmurt - physiologist V. M. Bekhterev, Komi - sociologist Pitirim Sorokin, Mordvin - sculptor S. Nefedov-Erzya, who took the name of the people as his pseudonym; Mari composer A. Ya. Eshpai.

ANCIENT CLOTHING V O D I I ZH O R T E V

The main part of the traditional women's costume of the Vodi and Izhorians is shirt

. Ancient shirts were sewn very long, with wide, also long sleeves. In the warm season, a shirt was the only clothing a woman could wear. Back in the 60s. XIX century After the wedding, the young woman was supposed to wear only a shirt until her father-in-law gave her a fur coat or caftan.

The main part of the traditional women's costume of the Vodi and Izhorians is shirt

. Ancient shirts were sewn very long, with wide, also long sleeves. In the warm season, a shirt was the only clothing a woman could wear. Back in the 60s. XIX century After the wedding, the young woman was supposed to wear only a shirt until her father-in-law gave her a fur coat or caftan.

Votic women long preserved the ancient form of unstitched waist clothing - hursgukset , which was worn over a shirt. Hursgukset is similar to Russian poneva. It was richly decorated with copper coins, shells, fringes, and bells. Later, when he came into everyday life sundress , the bride wore a hursgukset under a sundress to the wedding.

A kind of unstitched clothing - annua - worn in the central part Ingria(part of the territory of modern Leningrad region). It was a wide cloth that reached to the armpits; a strap was sewn to its upper ends and thrown over the left shoulder. The annua parted on the left side, and therefore a second cloth was put on under it - Khurstut . It was wrapped around the waist and also worn on a strap. The Russian sarafan gradually replaced the ancient loincloth among the Vodians and Izhorians. The clothes were belted leather belt, cords, woven belts and narrow towels.

In ancient times, Votic women shaved my head.

TRADITIONAL CLOTHING KH A N T O V I M A N S I

Khanty and Mansi clothes were made from skins, fur, fish skin, cloth, nettle and linen canvas. In the manufacture of children's clothing, they used the most archaic material - bird skins.

Khanty and Mansi clothes were made from skins, fur, fish skin, cloth, nettle and linen canvas. In the manufacture of children's clothing, they used the most archaic material - bird skins.

Men wore in winter swing fur coats made of deer and hare fur, squirrel and fox paws, and in summer a short robe made of coarse cloth; the collar, sleeves and right hem were trimmed with fur.Winter shoes It was made of fur and was worn with fur stockings. Summer made of rovduga (suede made from deer or elk skin), and the sole was made of elk skin.

Men's shirts they were sewn from nettle canvas, and the trousers were made from rovduga, fish skin, canvas, and cotton fabrics. Must be worn over a shirt woven belt , to which hung beaded bags(they held a knife in a wooden sheath and a flint).

Women wore in winter fur coat from deer skin; the lining was also fur. Where there were few deer, the lining was made from hare and squirrel skins, and sometimes from duck or swan down. In summer wore cloth or cotton robe ,decorated with stripes made of beads, colored fabric and tin plaques. The women cast these plaques themselves in special molds made of soft stone or pine bark. The belts were already men's and more elegant.

Women covered their heads both in winter and summer scarves with wide borders and fringes . In the presence of men, especially older relatives of the husband, according to tradition, the end of the scarf was supposed to be cover your face. They lived among the Khanty and beaded headbands .

Hair Previously, it was not customary to cut hair. Men parted their hair in the middle, gathered it into two ponytails and tied it with a colored cord. .Women braided two braids, decorated them with colored cord and copper pendants . At the bottom, the braids were connected with a thick copper chain so as not to interfere with work. Rings, bells, beads and other decorations were hung from the chain. Khanty women, according to custom, wore a lot copper and silver rings. Jewelry made from beads, which were imported by Russian merchants, were also widespread.

HOW THE MARIES DRESSED

In the past, Mari clothing was exclusively homemade. Upper(it was worn in winter and autumn) was sewn from homemade cloth and sheepskin, and shirts and summer caftans- made of white linen canvas.

In the past, Mari clothing was exclusively homemade. Upper(it was worn in winter and autumn) was sewn from homemade cloth and sheepskin, and shirts and summer caftans- made of white linen canvas.

Women wore shirt, caftan, trousers, headdress and bast shoes . Shirts were embroidered with silk, wool, and cotton threads. They were worn with belts woven from wool and silk and decorated with beads, tassels and metal chains. One of the types headdresses of married Maries , similar to a cap, was called shymaksh . It was made from thin canvas and placed on a birch bark frame. An obligatory part of the traditional costume of the Maries was considered jewelry made of beads, coins, tin plaques.

Men's suit consisted of canvas embroidered shirt, pants, canvas caftan and bast shoes . The shirt was shorter than a woman's and was worn with a narrow belt made of wool and leather. On head put on felt HATS and sheepskin caps .

WHAT IS FINNO-UGRIAN LINGUISTIC RELATIONSHIP

Finno-Ugric peoples differ from each other in their way of life, religion, historical destinies and even appearance. They are combined into one group based on the relationship of languages. However, linguistic proximity varies. The Slavs, for example, can easily come to an agreement, each speaking in his own dialect. But the Finno-Ugric people will not be able to communicate as easily with their brothers in the language group.

In ancient times, the ancestors of modern Finno-Ugrians spoke in one language. Then its speakers began to move, mixed with other tribes, and the once single language split into several independent ones. The Finno-Ugric languages diverged so long ago that they have few common words - about a thousand. For example, “house” in Finnish is “koti”, in Estonian – “kodu”, in Mordovian – “kudu”, in Mari – “kudo”. The word "butter" is similar: Finnish "voi", Estonian "vdi", Udmurt and Komi "vy", Hungarian "vaj". But the sound of the languages - phonetics - remains so close that any Finno-Ugric, listening to another and not even understanding what he is talking about, feels: this is a related language.

NAMES OF FINNO-UGRICS

Finno-Ugric peoples have been professing (at least officially) for a long time Orthodoxy , therefore their first and last names, as a rule, do not differ from Russians. However, in the village, in accordance with the sound of local languages, they change. So, Akulina becomes Oculus, Nikolai - Nikul or Mikul, Kirill - Kirlya, Ivan - Yivan. U Komi , for example, the patronymic is often placed before the given name: Mikhail Anatolyevich sounds like Tol Mish, i.e. Anatolyev's son Mishka, and Rosa Stepanovna turns into Stepan Rosa - Stepan's daughter Rosa. In the documents, of course, everyone has ordinary Russian names. Only writers, artists and performers choose the traditionally rural form: Yyvan Kyrlya, Nikul Erkay, Illya Vas, Ortjo Stepanov.

U Komi often found surnames Durkin, Rochev, Kanev; among the Udmurts - Korepanov and Vladykin; at Mordovians - Vedenyapin, Pi-yashev, Kechin, Mokshin. Surnames with a diminutive suffix are especially common among Mordovians - Kirdyaykin, Vidyaykin, Popsuykin, Alyoshkin, Varlashkin.

Some Mari , especially unbaptized chi-mari in Bashkiria, at one time they accepted turkic names. Therefore, the Chi-Mari often have surnames similar to Tatar ones: Anduga-nov, Baitemirov, Yashpatrov, but their names and patronymics are Russian. U Karelian There are both Russian and Finnish surnames, but always with a Russian ending: Perttuev, Lampiev. Usually in Karelia you can distinguish by surname Karelian, Finnish and St. Petersburg Finn. So, Perttuev - Karelian, Perttu - St. Petersburg Finn, A Pertgunen - Finn. But each of them can have a first and patronymic Stepan Ivanovich.

WHAT DO THE FINNO-UGRICS BELIEVE?

In Russia, many Finno-Ugrians profess Orthodoxy . In the 12th century. Vepsians were baptized in the 13th century. - Karelians, at the end of the 14th century. - Komi At the same time, to translate the Holy Scriptures into the Komi language, it was created Perm writing - the only original Finno-Ugric alphabet. During the XVIII-XIX centuries. Mordovians, Udmurts and Maris were baptized. However, the Maris never fully accepted Christianity. To avoid conversion to the new faith, some of them (they called themselves “chi-mari” - “true Mari”) went to the territory of Bashkiria, and those who stayed and were baptized often continued to worship the old gods. Among among the Mari, Udmurts, Sami and some other peoples, the so-called double faith . People revere the old gods, but recognize the “Russian God” and his saints, especially Nicholas the Pleasant. In Yoshkar-Ola, the capital of the Mari El Republic, the state took under protection a sacred grove - " kyusoto", and now pagan prayers take place here. The names of the supreme gods and mythological heroes of these peoples are similar and probably go back to the ancient Finnish name for the sky and air - " ilma ": Ilmarinen - among the Finns, Ilmayline - among the Karelians,Inmar - among the Udmurts, Yong -Komi.

CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE FINNO-UGRICS

Writing many Finno-Ugric languages of Russia were created on the basis Cyrillic alphabet, with the addition of letters and superscripts that convey sound features.Karelians , whose literary language is Finnish, are written in Latin letters.

Literature of the Finno-Ugric peoples of Russia very young, but oral folk art has a centuries-old history. Finnish poet and folklorist Elias Lönrö t (1802-1884) collected the tales of the epic " Kalevala "among the Karelians of the Olonets province of the Russian Empire. The final edition of the book was published in 1849. "Kalevala", which means "the country of Kalev", in its rune songs tells about the exploits of the Finnish heroes Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen and Lemminkäinen, about their struggle with the evil Louhi , mistress of Pohjola (northern country of darkness). In a magnificent poetic form, the epic tells about the life, beliefs, customs of the ancestors of the Finns, Karelians, Vepsians, Vodi, Izhorians. This information is unusually rich, they reveal the spiritual world of farmers and hunters of the North. "Kalevala" stands on a par with the greatest epics of humanity. Some other Finno-Ugric peoples also have epics: "Kalevipoeg"("Son of Caleb") - at Estonians , "Pera the hero" - y Komi-Permyaks , preserved epic tales among the Mordovians and Mansi .

The Finno-Ugric language group is part of the Ural-Yukaghir language family and includes the peoples: Sami, Vepsians, Izhorians, Karelians, Nenets, Khanty and Mansi.

Sami live mainly in the Murmansk region. Apparently, the Sami are the descendants of the oldest population of Northern Europe, although there is an opinion about their migration from the east. For researchers, the greatest mystery is the origin of the Sami, since the Sami and the Baltic-Finnish languages go back to a common base language, but anthropologically the Sami belong to a different type (Uralic type) than the Baltic-Finnish peoples, who speak languages that are closest to them related, but mainly of the Baltic type. To resolve this contradiction, many hypotheses have been put forward since the 19th century.

The Sami people most likely descend from the Finno-Ugric population. Presumably in the 1500-1000s. BC e. The separation of the proto-Sami begins from a single community of native language speakers, when the ancestors of the Baltic Finns, under Baltic and later German influence, began to move to a sedentary lifestyle as farmers and cattle breeders, while the ancestors of the Sami in Karelia assimilated the autochthonous population of Fennoscandia.

The Sami people, in all likelihood, were formed by the merger of many ethnic groups. This is indicated by anthropological and genetic differences between the Sami ethnic groups living in different territories. Genetic studies in recent years have revealed that modern Sami have common features with the descendants of the ancient population of the Atlantic coast of the Ice Age - the modern Basque Berbers. Such genetic characteristics were not found in more southern groups of Northern Europe. From Karelia, the Sami migrated further and further north, fleeing the spreading Karelian colonization and, presumably, tribute. Following the migrating herds of wild reindeer, the ancestors of the Sami, at the latest during the 1st millennium AD. e., gradually reached the coast of the Arctic Ocean and reached the territories of their current residence. At the same time, they began to move on to breeding domesticated reindeer, but this process reached a significant extent only in the 16th century.

Their history over the past one and a half millennia represents, on the one hand, a slow retreat under the onslaught of other peoples, and on the other hand, their history is an integral part of the history of nations and peoples that have their own statehood in which an important role is given to the imposition of tribute on the Sami. A necessary condition for reindeer herding was that the Sami wandered from place to place, driving herds of reindeer from winter to summer pastures. In practice, nothing prevented people from crossing state borders. The basis of the Sami society was a community of families, which were united on the principles of joint ownership of land, which gave them the means to subsist. Land was allocated by family or clan.

Figure 2.1 Dynamics of the population of the Sami people 1897 – 2010 (compiled by the author based on materials).

Izhorians. The first mention of Izhora occurs in the second half of the 12th century, where it speaks of pagans, who half a century later were already recognized in Europe as a strong and even dangerous people. It was from the 13th century that the first mentions of Izhora appeared in Russian chronicles. In the same century, the Izhora land was first mentioned in the Livonian Chronicle. At dawn of a July day in 1240, the elder of the Izhora land, while on patrol, discovered the Swedish flotilla and hastily sent a report to Alexander, the future Nevsky, about everything.

Obviously, at this time the Izhorians were still very close ethnically and culturally to the Karelians who lived on the Karelian Isthmus and in the Northern Ladoga region, north of the area of the supposed distribution of the Izhorians, and this similarity persisted until the 16th century. Quite accurate data on the approximate population of the Izhora land were first recorded in the Scribe Book of 1500, but the ethnicity of the residents was not shown during the census. It is traditionally believed that the inhabitants of the Karelian and Orekhovetsky districts, most of whom had Russian names and nicknames of Russian and Karelian sound, were Orthodox Izhorians and Karelians. Obviously, the border between these ethnic groups passed somewhere on the Karelian Isthmus, and perhaps coincided with the border of Orekhovetsky and Karelian counties.

In 1611, Sweden took possession of this territory. During the 100 years that this territory became part of Sweden, many Izhorians left their villages. Only in 1721, after the victory over Sweden, Peter I included this region in the St. Petersburg province of the Russian state. At the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, Russian scientists began to record the ethno-confessional composition of the population of the Izhora lands, then already included in the St. Petersburg province. In particular, to the north and south of St. Petersburg, the presence of Orthodox residents is recorded, ethnically close to the Finns - Lutherans - the main population of this territory.

Veps. At present, scientists cannot finally resolve the question of the genesis of the Veps ethnic group. It is believed that by origin the Vepsians are associated with the formation of other Baltic-Finnish peoples and that they separated from them, probably in the 2nd half. 1 thousand n. e., and by the end of this thousand settled in the southeastern Ladoga region. The burial mounds of the 10th-13th centuries can be defined as ancient Vepsian. It is believed that the earliest mentions of the Vepsians date back to the 6th century AD. e. Russian chronicles from the 11th century call this people the whole. Russian scribal books, lives of saints and other sources more often know the ancient Vepsians under the name Chud. The Vepsians lived in the interlake region between Lakes Onega and Lake Ladoga from the end of the 1st millennium, gradually moving east. Some groups of Vepsians left the inter-lake region and merged with other ethnic groups.

In the 1920s and 30s, Vepsian national districts, as well as Veps rural councils and collective farms, were created in places where people lived compactly.

In the early 1930s, the introduction of teaching the Vepsian language and a number of academic subjects in this language in primary schools began, and Vepsian language textbooks based on Latin script appeared. In 1938, Vepsian-language books were burned, and teachers and other public figures were arrested and expelled from their homes. Since the 1950s, as a result of increased migration processes and the associated spread of exogamous marriages, the process of assimilation of the Vepsians has accelerated. About half of the Vepsians settled in cities.

Nenets. History of the Nenets in the 17th-19th centuries. rich in military conflicts. In 1761, a census of yasak foreigners was carried out, and in 1822, the “Charter on the management of foreigners” was put into effect.

Excessive monthly exactions and the arbitrariness of the Russian administration have repeatedly led to riots, accompanied by the destruction of Russian fortifications; the most famous is the Nenets uprising in 1825-1839. As a result of military victories over the Nenets in the 18th century. first half of the 19th century The area of settlement of the tundra Nenets expanded significantly. By the end of the 19th century. The territory of Nenets settlement has stabilized, and their numbers have increased compared to the end of the 17th century. approximately doubled. Throughout the Soviet period, the total number of Nenets, according to census data, also increased steadily.

Today the Nenets are the largest of the indigenous peoples of the Russian North. The share of Nenets who consider the language of their nationality to be their native language is gradually decreasing, but still remains higher than that of most other peoples of the North.

Figure 2.2 Number of Nenets peoples 1989, 2002, 2010 (compiled by the author based on materials).

In 1989, 18.1% of Nenets recognized Russian as their native language, and in general were fluent in Russian, 79.8% of Nenets - thus, there is still a fairly noticeable part of the linguistic community, adequate communication with which can only be ensured by knowledge of the Nenets language. It is typical that young people retain strong Nenets speech skills, although for a significant part of them the Russian language has become the main means of communication (as with other peoples of the North). A certain positive role is played by the teaching of the Nenets language at school, the popularization of national culture in the media, and the activities of Nenets writers. But first of all, the relatively favorable language situation is due to the fact that reindeer husbandry - the economic basis of Nenets culture - was generally able to survive in its traditional form despite all the destructive trends of the Soviet era. This type of production activity remained entirely in the hands of the indigenous population.

Khanty- a small indigenous Ugric people living in the north of Western Siberia. There are three ethnographic groups of Khanty: northern, southern and eastern, and the southern Khanty mixed with the Russian and Tatar population. The ancestors of the Khanty penetrated from the south into the lower reaches of the Ob and settled the territories of modern Khanty-Mansiysk and the southern regions of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and from the end of the 1st millennium, based on the mixing of aborigines and alien Ugric tribes, the ethnogenesis of the Khanty began. The Khanty called themselves more by rivers, for example “people of Konda”, “people of the Ob”.

Northern Khanty. Archaeologists associate the genesis of their culture with the Ust-Polui culture, localized in the river basin. Ob from the mouth of the Irtysh to the Ob Bay. This is a northern, taiga fishing culture, many of whose traditions are not followed by modern northern Khanty.

From the middle of the 2nd millennium AD. The northern Khanty were strongly influenced by the Nenets reindeer herding culture. In the zone of direct territorial contacts, the Khanty were partially assimilated by the tundra Nenets.

Southern Khanty. They spread upward from the mouth of the Irtysh. This is the territory of the southern taiga, forest-steppe and steppe and culturally it gravitates more to the south. In their formation and subsequent ethnocultural development, the southern forest-steppe population played a significant role, layering on the general Khanty base. The Russians had a significant influence on the southern Khanty.

Eastern Khanty. They settle in the Middle Ob region and along the tributaries: Salym, Pim, Agan, Yugan, Vasyugan. This group, to a greater extent than others, retains North Siberian cultural features dating back to the Ural population - draft dog breeding, dugout boats, the predominance of swing clothing, birch bark utensils, and a fishing economy. Within the modern territory of their habitat, the Eastern Khanty interacted quite actively with the Kets and Selkups, which was facilitated by belonging to the same economic and cultural type.

Thus, in the presence of common cultural features characteristic of the Khanty ethnic group, which is associated with the early stages of their ethnogenesis and the formation of the Ural community, which, along with the mornings, included the ancestors of the Kets and Samoyed peoples, the subsequent cultural “divergence”, the formation of ethnographic groups, to a greater extent was determined by the processes of ethnocultural interaction with neighboring peoples. Muncie- a small people in Russia, the indigenous population of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug. Closest relatives of the Khanty. They speak the Mansi language, but due to active assimilation, about 60% use Russian in everyday life. As an ethnic group, the Mansi were formed as a result of the merger of local tribes of the Ural culture and Ugric tribes moving from the south through the steppes and forest-steppes of Western Siberia and Northern Kazakhstan. The two-component nature (a combination of the cultures of taiga hunters and fishermen and steppe nomadic herders) in the culture of the people persists to this day. Initially, the Mansi lived in the Urals and its western slopes, but the Komi and Russians in the 11th-14th centuries forced them out into the Trans-Urals. The earliest contacts with Russians, primarily Snovgorodians, date back to the 11th century. With the annexation of Siberia to the Russian state at the end of the 16th century, Russian colonization intensified, and already at the end of the 17th century the number of Russians exceeded the number of the indigenous population. The Mansi were gradually forced out to the north and east, partially assimilated, and were converted to Christianity in the 18th century. The ethnic formation of Mansi was influenced by various peoples.

In the Vogul cave, located near the village of Vsevolodo-Vilva in the Perm region, traces of Voguls were discovered. According to local historians, the cave was a temple (pagan sanctuary) of the Mansi, where ritual ceremonies were held. In the cave, bear skulls with traces of blows from stone axes and spears, shards of ceramic vessels, bone and iron arrowheads, bronze plaques of the Permian animal style with an image of an elk man standing on a lizard, silver and bronze jewelry were found.

Among those living on the planet today there are many unique, original and even somewhat mysterious peoples and nationalities. These, undoubtedly, include the Finno-Ugric peoples, who are considered the largest ethno-linguistic community in Europe. It includes 24 nations. 17 of them live in the Russian Federation.

Composition of the ethnic group

All the numerous Finno-Ugric peoples are divided by researchers into several groups:

- Baltic-Finnish, the backbone of which consists of quite numerous Finns and Estonians, who formed their own states. This also includes the Setos, Ingrians, Kvens, Vyrs, Karelians, Izhorians, Vepsians, Vods and Livs.

- Sami (Lapp), which includes residents of Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula.

- Volga-Finnish, which includes the Mari and Mordovians. The latter, in turn, are divided into Moksha and Erzya.

- Perm, which includes Komi, Komi-Permyaks, Komi-Zyryans, Komi-Izhemtsy, Komi-Yazvintsy, Besermyans and Udmurts.

- Ugorskaya. It includes the Hungarians, Khanty and Mansi, separated by hundreds of kilometers.

Vanished Tribes

Among the modern Finno-Ugric peoples there are numerous peoples, and very small groups - less than 100 people. There are also those whose memory is preserved only in ancient chronicle sources. The disappeared, for example, include Merya, Chud and Muroma.

The Meryans built their settlements between the Volga and Oka several hundred years BC. According to some historians, this people subsequently assimilated with the East Slavic tribes and became the progenitor of the Mari people.

An even more ancient people were the Muroma, who lived in the Oka basin.

As for the Chud, this people lived along the Onega and Northern Dvina. There is an assumption that these were ancient Finnish tribes from which modern Estonians descended.

Regions of settlement

The Finno-Ugric group of peoples today is concentrated in northwestern Europe: from Scandinavia to the Urals, Volga-Kama, West Siberian Plain in the lower and middle reaches of the Tobol.

The only people who formed their own state at a considerable distance from their brethren are the Hungarians living in the Danube basin in the Carpathian Mountains region.

The most numerous Finno-Ugric people in Russia are the Karelians. In addition to the Republic of Karelia, many of them live in the Murmansk, Arkhangelsk, Tver and Leningrad regions of the country.

Most of the Mordovians live in the Republic of Mordva, but many of them also settled in neighboring republics and regions of the country.

In these same regions, as well as in Udmurtia, Nizhny Novgorod, Perm and other regions, you can also meet Finno-Ugric peoples, especially many Mari here. Although their main backbone lives in the Republic of Mari El.

The Komi Republic, as well as nearby regions and autonomous okrugs, is the place of permanent residence of the Komi people, and in the Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug and the Perm region live their closest “relatives” - the Komi-Permyaks.

More than a third of the population of the Udmurt Republic are ethnic Udmurts. In addition, there are small communities in many nearby regions.

As for the Khanty and Mansi, the bulk of them live in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug. In addition, large Khanty communities live in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug and the Tomsk region.

Appearance type

Among the ancestors of the Finno-Ugrians there were both ancient European and ancient Asian tribal communities, so in the appearance of modern representatives one can observe features inherent in both the Mongoloid and Caucasian races.

General features of the distinctive features of representatives of this ethnic group include average height, very light hair, wide cheekbones with an upturned nose.

Moreover, each nationality has its own “variations”. For example, the Erzya Mordvins are much taller than average, but at the same time have pronounced blue-eyed blond hair. But the Moksha Mordvins, on the contrary, are short, and their hair color is darker.

The Udmurts and Maris have “Mongolian type” eyes, which makes them similar to the Mongoloid race. But at the same time, the vast majority of representatives of the nationality are fair-haired and light-eyed. Similar facial features are also found among many Izhorians, Karelians, Vodians, and Estonians.

But Komi can be either dark-haired with slanted eyes, or fair-haired with pronounced Caucasian features.

Quantitative composition

In total, there are about 25 million Finno-Ugric people living in the world. The most numerous of them are Hungarians, who number more than 15 million. Finns are almost three times less - about 6 million, and the number of Estonians is a little more than a million.

The number of other nationalities does not exceed a million: Mordovians - 843 thousand; Udmurts - 637 thousand; Mari - 614 thousand; Ingrians - just over 30 thousand; Kvens - about 60 thousand; Võru - 74 thousand; setu - about 10 thousand, etc.

The smallest nationalities are the Livs, whose number does not exceed 400 people, and the Vods, whose community consists of 100 representatives.

An excursion into the history of the Finno-Ugric peoples

There are several versions about the origin and ancient history of the Finno-Ugric peoples. The most popular of them is the one that assumes the existence of a group of people who spoke the so-called Finno-Ugric proto-language, and maintained their unity until approximately the 3rd millennium BC. This Finno-Ugric group of peoples lived in the Urals and western Urals region. In those days, the ancestors of the Finno-Ugrians maintained contact with the Indo-Iranians, as evidenced by all kinds of myths and languages.

Later, the single community split into Ugric and Finno-Perm. From the second, the Baltic-Finnish, Volga-Finnish and Permian language subgroups subsequently emerged. Separation and isolation continued until the first centuries of our era.

Scientists consider the homeland of the ancestors of the Finno-Ugrians to be the region located on the border of Europe with Asia in the interfluve of the Volga and Kama, the Urals. At the same time, the settlements were located at a considerable distance from each other, which may have been the reason that they did not create their own unified state.

The main occupations of the tribes were agriculture, hunting and fishing. The earliest mentions of them are found in documents from the times of the Khazar Kaganate.

For many years, Finno-Ugric tribes paid tribute to the Bulgar khans and were part of the Kazan Khanate and Rus'.

In the 16th-18th centuries, the territory of Finno-Ugric tribes began to be settled by thousands of immigrants from various regions of Rus'. The owners often resisted such an invasion and did not want to recognize the power of the Russian rulers. The Mari resisted especially fiercely.

However, despite the resistance, gradually the traditions, customs and language of the “newcomers” began to supplant local speech and beliefs. Assimilation intensified during subsequent migration, when Finno-Ugrians began to move to various regions of Russia.

Finno-Ugric languages

Initially, there was a single Finno-Ugric language. As the group divided and different tribes settled further and further from each other, it changed, breaking up into separate dialects and independent languages.

Until now, Finno-Ugric languages have been preserved by both large nations (Finns, Hungarians, Estonians) and small ethnic groups (Khanty, Mansi, Udmurts, etc.). Thus, in the primary classes of a number of Russian schools, where representatives of the Finno-Ugric peoples study, they study the Sami, Khanty and Mansi languages.

Komi, Mari, Udmurts, and Mordovians can also study the languages of their ancestors, starting from middle school.

Other peoples speaking Finno-Ugric languages, may also speak dialects similar to the main languages of the group they belong to. For example, the Besermen speak one of the dialects of the Udmurt language, the Ingrians speak the eastern dialect of Finnish, the Kvens speak Finnish, Norwegian or Sami.

Currently, there are barely a thousand common words in all the languages of the peoples belonging to the Finno-Ugric peoples. Thus, the “family” connection between different peoples can be traced in the word “home”, which among the Finns sounds like koti, among the Estonians - kodu. “Kudu” (Mor.) and “Kudo” (Mari) have a similar sound.

Living next to other tribes and peoples, the Finno-Ugric peoples adopted culture and language from them, but also generously shared their own. For example, “rich and powerful” includes Finno-Ugric words such as “tundra”, “sprat”, “herring” and even “dumplings”.

Finno-Ugric culture

Archaeologists find cultural monuments of the Finno-Ugric peoples in the form of settlements, burials, household items and jewelry throughout the entire territory inhabited by the ethnic group. Most of the monuments date back to the beginning of our era and the early Middle Ages. Many peoples have managed to preserve their culture, traditions and customs until today.

Most often they manifest themselves in various rituals (weddings, folk festivals, etc.), dances, clothing and everyday life.

Literature

Finno-Ugric literature is conventionally divided by historians and researchers into three groups:

- Western, which includes works of Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian writers and poets. This literature, which was influenced by the literature of European peoples, has the richest history.

- Russian, the formation of which begins in the 18th century. It includes works by authors of the Komi, Mari, Mordovians, and Udmurts.

- Northern. The youngest group, developed only about a century ago. It includes works by Mansi, Nenets, and Khanty authors.

At the same time, all representatives of the ethnic group have a rich heritage of oral folk art. Every nationality has numerous epics and legends about heroes of the past. One of the most famous works of folk epic is “Kalevala,” which tells about the life, beliefs and customs of our ancestors.

Religious preferences

Most of the peoples belonging to the Finno-Ugrians profess Orthodoxy. Finns, Estonians and Western Sami adhere to the Lutheran faith, while Hungarians adhere to the Catholic faith. At the same time, ancient traditions are preserved in rituals, mostly wedding ones.

But the Udmurts and Mari in some places still preserve their ancient religion, just as the Samoyeds and some peoples of Siberia worship their gods and practice shamanism.

Features of national cuisine

In ancient times, the main food product of the Finno-Ugric tribes was fish, which was fried, boiled, dried and even eaten raw. Moreover, each type of fish had its own cooking method.

The meat of forest birds and small animals caught in snares was also used as food. The most popular vegetables were turnips and radishes. The food was richly seasoned with spices such as horseradish, onions, hogweed, etc.

The Finno-Ugric peoples prepared porridges and jelly from barley and wheat. They were also used to fill homemade sausages.

Modern Finno-Ugric cuisine, which has been strongly influenced by neighboring peoples, has almost no special traditional features. But almost every nation has at least one traditional or ritual dish, the recipe for which has been handed down to the present day almost unchanged.

A distinctive feature of the cuisine of the Finno-Ugric peoples is that in food preparation preference is given to products grown in the place where the people live. But imported ingredients are used only in the smallest quantities.

Save and increase

In order to preserve the cultural heritage of the Finno-Ugric peoples and pass on the traditions and customs of their ancestors to future generations, all kinds of centers and organizations are being created everywhere.

Much attention is paid to this in the Russian Federation. One of such organizations is the non-profit association Volga Center of Finno-Ugric Peoples, created 11 years ago (April 28, 2006).

As part of its work, the center not only helps large and small Finno-Ugric peoples not to lose their history, but also introduces it to other peoples of Russia, helping to strengthen mutual understanding and friendship between them.

Famous representatives

Like every nation, the Finno-Ugric peoples have their own heroes. A well-known representative of the Finno-Ugric people is the nanny of the great Russian poet, Arina Rodionovna, who was from the Ingrian village of Lampovo.

Also Finno-Ugrians are such historical and modern figures as Patriarch Nikon and Archpriest Avvakum (both were Mordvins), physiologist V. M. Bekhterev (Udmurt), composer A. Ya. Eshpai (Mari), athlete R. Smetanina (Komi) and many others.

| The Finno-Ugric peoples form part of a unique family of diverse cultures, possessing languages, cultural and artistic traditions that form a special, unique piece of the beautiful mosaic of humanity. The linguistic kinship of the Finno-Ugric peoples was discovered by the Hungarian Catholic priest Janos Shajnovic (1733-1785). Today, Finno-Ugrians constitute one branch of a large family of Uralic languages, which also includes the Samoyedic branch (Nenets, Enets, Nganasans and Selkups). According to the 2002 census of the Russian Federation, 2,650,402 people recognized themselves as Finno-Ugric. However, experience shows that in all likelihood a large number of ethnic Finno-Ugric people, perhaps even half, chose to call themselves Russian. Thus, the total number of Finno-Ugric people living in Russia is actually 5 million people or more. If we add Estonians, Finns, Hungarians and Sami to this number, the number of Finno-Ugric people living on our planet will exceed 26 million! This means that there are approximately the same number of Finno-Ugric people as there are residents of Canada! |

2 Udmurts, 1 Estonian, 2 Komi, 2 Mordvinian |

Who are the Finno-Ugrians?

It is believed that the ancestral home of the Finno-Ugric peoples is located to the west of the Ural Mountains, in the region of Udmurtia, Perm, Mordovia and Mari El. By 3000 BC. e. The Baltic-Finnish subgroup moved west along the Baltic Sea coast. Around the same time, the Sami moved inland to the northeast, reaching the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. The Magyars (Hungarians) made the longest and most recent journey from the territory of the Ural Mountains to their real homeland in central Europe, only in 896 AD. e.

What is the age of the Finno-Ugric peoples?

The culture of pit-comb ceramics (The name was given by the method of decorating ceramic finds characteristic of this culture, which looks like imprints of combs.), which reached its peak in 4200 - 2000 BC. e. between the Urals and the Baltic Sea, generally appears as the oldest clear evidence of early Finno-Ugric communities. Settlements of this culture are always accompanied by burials of representatives of the Ural race, in the phenotype of which a mixture of Mongoloid and Caucasian elements is found.

But does the culture of pit-comb ceramics represent the beginning of the life of the Finno-Ugric people or is this distinctive pattern just a new artistic tradition among the already old Finno-Ugric civilization?

So far, archaeologists do not have an answer to this question. They discovered settlements in the area that date back to before the end of the last ice age, but so far scientists do not have sufficient evidence to suggest that these were settlements of Finno-Ugric or other peoples known to us. Since two or more peoples may live in the same territory, geographical information alone is not sufficient. In order to establish the identity of these settlements, it is necessary to show a certain connection, for example, similar artistic traditions, which are an indicator of a common culture. Since these early settlements are 10,000 years old, archaeologists simply do not have enough evidence to make any assumptions, so the origins of these settlements remain a mystery. What is the age of the Finno-Ugric peoples? At present it is impossible to give an exact answer to this question. We can only say that the Finno-Ugrians appeared in the west of the Ural Mountains between the end of the last Ice Age and 8000 - 4200 BC. e.

Let's look at this period of time in perspective:

Writing was invented by the Sumerians around 3800 BC. e.

The Egyptian pyramids were built in 2500 BC. e.

Stonehenge in England was built in 2200 BC. e.

The Celts, ancestors of the Irish and Scots, landed on the British Isles around 500 BC. e.

The English landed on the British Isles after 400 AD. e.

The Turks began moving into the territory of modern Turkey around 600 AD. e.

As a result, anthropologists call the Finno-Ugric peoples the oldest permanent inhabitants of Europe and the oldest surviving inhabitants of northeastern Europe.

However, it is no longer possible to separate the history of the Finno-Ugrians from the history of another people, the Indo-European Slavs.

By 600 AD e. the Slavs were divided into three branches: southern, western and eastern. A slow process of resettlement and resettlement began. In the 9th century, the Eastern Slavs formed a center in Kievan Rus and Novgorod. By the mid-16th century, with the conquest of the Kazan Khanate by Russia, almost all Finno-Ugric peoples, not counting the Sami, Finns, Estonians and Hungarians, came under the control of Rus'.

Today, the majority of Finno-Ugric people live on the territory of the Russian Federation, and their future is forever linked with their large Slavic neighbor.

Finno-Ugric languages

“Language diversity is an integral part of humanity's heritage. Each language embodies the unique cultural wisdom of a people. Thus, the loss of any language is a loss for all humanity.”

UNESCO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

Estonian philologist Mall Hellam found only one sentence understandable in the three most common Finno-Ugric languages: Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian. Live fish swims in the water

"Eleven hal úszkál a víz alatt." (Hungarian)

"Elävä kala ui veden alla." (Finnish)

"Elav kala ujub vee all." (Estonian)

To these languages you can add Erzya “Ertstsya kaloso ukshny after all alga” (Erzya)

The Finno-Ugric languages usually include the following groups and languages:

| Number of speakers | Total number of people | According to UNESCO: | ||

| Ugric subbranch | Hungarian | 14 500 000 | 14 500 000 | Prosperous |

| Khanty | 13 568 | 28 678 | Dysfunctional | |

| Mansi | 2 746 | 11 432 | Vanishing | |

| Finno-Permian subbranch | Udmurt | 463 837 | 636 906 | Dysfunctional |

| Komi-Zyryansky | 217 316 | 293 406 | Dysfunctional | |

| Komi-Permyak | 94 328 | 125 235 | Dysfunctional | |

| Finno-Volga languages | Erzya-Mordovian | 614 260 | 843 350 | Dysfunctional |

| Moksha-Mordovian | Dysfunctional | |||

| Lugovo-Mari | 451 033 | 604 298 | Dysfunctional | |

| Gorno-Mari | 36 822 | Dysfunctional | ||

| Finnish | 5 500 000 | 5 500 000 | Prosperous | |

| Estonian | 1 000 000 | 1 000 000 | Prosperous | |

| Karelian | 52 880 | 93 344 | Dysfunctional | |

| Aunus Karelian | Dysfunctional | |||

| Vepsian | 5 753 | 8 240 | Vanishing | |

| Izhora | 362 | 327 | Vanishing | |

| Vodsky | 60 | 73 | Almost extinct | |

| Livsky | 10 | 20 | Almost extinct | |

| Western Sami cluster | Northern Sami | 15 000 | 80 000* | Dysfunctional |

| Lule Sami | 1 500 | Vanishing | ||

| South Sami | 500 | Vanishing | ||

| Pite Sami | 10-20 | Almost extinct | ||

| Ume Sami | 10-20 | Almost extinct | ||

| Eastern Sami cluster | Kildinsky | 787 | Vanishing | |

| Inari-Sami | 500 | Vanishing | ||

| Kolta Sami | 400 | Vanishing | ||

| Terek-Sami | 10 | Almost extinct | ||

| Akkala | - | Extinct December 2003 | ||

| Kemi-Sami | - | Extinct in the 19th century. |

Compare Finno-Ugric languages

As in any family, some members are more similar to each other, and some are only vaguely similar. But we are united by our common linguistic roots, this is what defines us as a family and creates the basis for discovering cultural, artistic and philosophical connections.

Counting in Finno-Ugric languages

| Finnish | yksi | kaksi | kolme | nelj | viisi | kuusi | seitsemän | kahdeksan | yhkeksän | kymmenen |

| Estonian | üks | kaks | kolm | neli | viis | kuus | seitse | kaheksa | üheksa | kümme |

| Vepsian | ükś | kakś | koume | nel" | viž | kuź | seičeme | kahcan | ühcan | kümńe |

| Karelian | yksi | kaksi | kolme | nelli | viizi | kuuzi | seicččie | kaheka | yheks | kymmene |

| Komi | These | kick | quim | nel | vit | Quiet | sisim | kokyamys | Okmys | yes |

| Udmurt | odӥg | kick | quinh | Nyeul | twist | hammer | blue | Tyamys | ukmys | yes |

| Erzya | vake | car | Colmo | Nile | vete | koto | systems | kavxo | weixe | kemen |

| Moksha | ||||||||||

| Lugovo-Marisky | IR | cook | godfather | whined | hiv | where | shym | pencil | Indian | lu |

| Hungarian | egy | kett | harom | négy | ot | hat | het | nyolc | kilenc | tiz |

| Khanty | it | katn | Hulme | nyal | vet | hoot | lapat | Neil | yartyang | young |

| Northern Sami | okta | guokte | golbma | njeallje | vihtta | guhtta | čieža | gávcci | ovcci | logi |

| Finno-Ugic prototype |

ykte | kakte | kolm- | neljä- | vit(t)e | kut(t)e | - | - | - | - |

Common Finno-Ugric words

| heart | hand | eye | blood | go | fish | ice | |

| Finnish | sydan | käsi | silm | veri | menn | kala | jää |

| Estonian | süda | käsi | silm | veri | mine | kala | jää |

| Komi | go home | ki | syn | vir | mun | cherry | yee |

| Udmurt | sulum | ki | syn | we N | choryg | йӧ | |

| Erzya | gray hairs | kedy | selma | believe | molems | feces | Hey |

| Lugovo-Marisky | noise | kid | shincha | thief | miyash | count | th |

| Hungarian | szív | kez | szem | ver | menni | hal | jég |

| Khanty | myself | Yesh | Sam | vur | mana | blasphemy | engk |

| Northern Sami | giehta | čalbmi | mannat | guolli | jiekŋa | ||

| Finno-Ugic prototype |

śiδä(-mɜ) | kate | śilmä | mene- | kala | jŋe |

Finno-Ugric personal pronouns

|

Baltic-Finnish subgroup |

Finno-Permian |

||||||

| Finnish | Karelian | Livvikovsky | Vepsian | Estonian | Udmurt | Komi | |

| I | min | mie | min | min | mina | mon | meh |

| You | sin | sie | sin | sin | sina | tone | te |

| he she | hän | hiän | häi | hän | theme | with | siyo |

| We | me | my | müö | mö | meie | mi | mi |

| You | te | työ | tüö | tö | teie | tӥ | ti |

| They | he | hyö | hüö | hö | nemad | soos | nayö |

|

Finno-Volga languages |

Ugric subbranch |

||||||

| Mordovians |

Mari |

Hungarian | Khanty | ||||

| Erzya |

Lugovo- |

||||||

| I | mon | washed | en | ma | |||

| You | tone | ty | te | nang | |||

| he she | dream | tudo | õ | luv | |||

| We | ming | meh | mi | mung/min | |||

| You | tink | those | ti | now | |||

| They | son | Nuno | õk | luv/lyn | |||