Roman Empire: flag, coat of arms, emperors, events. History of the Roman Empire What cities existed during the era of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire united large areas of Europe for the first time. Its institutional and political structure continues to influence and serve as a model for many countries to this day.

Founding of Rome

According to legend, Rome was founded by Romulus and Remus in 753 BC. e. The twin sons of Mars were abandoned in infancy and raised by a she-wolf. Romulus killed his brother in a dispute over the location of the new city and became the first ruler of a powerful, feared family. It is believed that at the end of Romulus' life, Mars was carried away by a thundercloud and made the god Quirinus.

In reality, people lived on the territory of Rome for thousands of years. The early Romans created a well-organized community. They allied with neighboring Latin tribes to overthrow the dominant Etruscans. Around 265 BC. The Romans subjugated all of Italy and developed a highly differentiated social and military system. From the ranks of the nobility, to which the Etruscans also belonged, a king was appointed. The monarchy, founded, according to legend, by Romulus, ended its existence in 510 BC, when the tyrant Tarquin the Proud was expelled and the Roman Republic was created.

Republic

To prevent new tyranny, the Romans introduced a republican system of government. The powers previously owed to the king were transferred to two consuls, elected annually from the ranks of the Senate. The senators themselves were high-ranking magistrates who took office through democratic elections. Subsequently, this system became the prototype of the US Constitution. The Republic brought stability and then prosperity to Rome. Rome usually made defeated Italian city-states its allies, and in return for providing troops, their citizens were guaranteed Roman citizenship rights.

Punic Wars

As their influence in the Mediterranean grew, the Romans became a threat to the powerful kingdom of Carthage in North Africa. The first of the Punic Wars began in 264 BC. and ended with Carthage falling and Rome capturing its territories. Hannibal's attack in Spain and his march on war elephants through the Alps into upper Italy started the Second Punic War. After the Roman general Cornelius Scipio defeated Hannibal and the Carthaginians, Rome made Spain a province in its growing colonial state. The creation of a powerful fleet allowed the Romans to make long-distance conquests, and in 31 BC. e. Rome included all the Mediterranean lands in its empire: Greece, Cyprus and Asia Minor.

Religion and gods

The veneration of gods and religious cults were important factors in the life of the Romans. The Roman religion was based on Greek mythology, but the Romans gave the Greek gods their own names and added new qualities and titles to them. Jupiter, being the supreme deity of the Roman pantheon, played such an important role that before every political action it was considered necessary to consult him. The Lord of thunder and lightning, with the help of celestial signs such as weather phenomena and flocks of birds, revealed their future to people. Since Jupiter could also influence the course of history, rituals were regularly performed in his honor. his wife Juno was considered the patroness of women and family. Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and patroness of artisans, according to myth, came out of the head of Jupiter in full armor. And the god of wars, Mars, was one of the gods significant to the Romans. Since at first he was associated with fertility, the spring month of March received its name by name. Janus, the god of gates, entrances and exits, was depicted as double-headed, that is, he was able to look in both directions. Associated with the beginning of all events, God gave his name to January - the first calendar month. Neptune corresponded to the Greek sea god Poseidon and the cover testified to all sailors. These and many other deities were regularly honored, and on certain days dedicated to them, festivities were held in their honor. Temples were built as places of religious worship, as well as for rituals and sacrifices. The constant expansion of the borders of Roman possessions led to the borrowing and integration of foreign cults and religions. Thus, the Egyptian goddess Isis and the Persian sun god Mithra firmly entered into Roman culture.

Empire

In 82 BC. the commander Sulla forced the Roman Senate to grant him dictatorial rights for ten years. The expansion of Rome throughout the then known world meant for the Republic that it became increasingly dependent on the power of its army, and, consequently, on its military leaders. At this time, tension in the political and social sphere increased, and unrest occurred that destabilized the republic. Some military leaders followed Sulla's example and competed for power in the state, including Julius Caesar, a brilliant politician and commander who led the Senate in a triumvirate with Pompey and Crassius. Caesar used all means to remove his comrades Pompey and Crassius from the game and in 44 BC. achieved autocracy. A conspiracy of Republican senators led by Brutus, which resulted in Caesar's assassination, brought an end to his regime. Caesar saw his nephew Octavian as a successor, but the Senate appointed Mark Antony in his place. However, it was not possible to resolve the internal political unrest. When Anthony entered into an alliance with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, Octavian, using this as a pretext, went against his rival and in 31 BC. e. defeated him at the Battle of Actium. Today this date is considered the birthday of the Roman Empire. In 27 BC. e. The Senate gives Octavian the honorary name "Augustus". Octavian chose the title of "princesses" ("first") to maintain the appearance of democracy, but in fact enjoyed the powers of an autocrat and ruled the Roman Empire as the first emperor from 27 BC. to 14 AD e.

The Augustan era was considered a Golden Age during which the empire grew, political stability reigned, and culture and art flourished. Augustus himself said that he “took Rome as clay, but left it as marble.” After his death, Augustus was deified. Although his successor Tiberius ensured stability in the state, the status of the emperor was still fragile, since there was no succession regulated by law. Caligula and Claudius, the emperors who followed Tiberius, were killed, and the maddened tyrant Nero was expelled from the throne.

Emperor Vespasian (69-79 AD) marked the beginning of a new dynasty of rulers. Under Vespasian, Rome acquired its characteristic architectural appearance; it was on his order that the Colosseum was erected.

The Colosseum was originally called the Flavian Amphitheatre, and later received its current name - Colosseum - because of the colossal statue of Nero located there.

His son, Emperor Domitian, who was assassinated in 96 AD, ordered the floors and walls of his palace to be lined with polished marble, sources say, so that possible murderers would have nowhere to hide. Under Hadrian (117-131 AD), the Roman Empire expanded its territories to the greatest extent in its history. The following decades were marked by wars with enemies on the outer borders of the Empire. In 476 AD. The last emperor, Romulus Augustus, was overthrown by East German troops.

The Birth of Christianity

Under Emperor Augustus, Rome strengthened its dominant position in Palestine with the help of Herod the Great, whom the Romans appointed as their governor in Judea. When Jesus preached his teachings in Nazareth and promised people salvation in the Kingdom of Heaven, at first he found widespread support. The message spread by Jesus and his twelve disciples met with special interest among the common people, since they suffered under the rule of the Romans.

However, the Jewish priests regarded Jesus' preaching about salvation as sacrilege, and the Romans saw him as a rebel.

Because of his attacks on the ruling classes and their growing influence, he fell out of favor and was taken into custody. Although Christ's activity, which lasted about three years, was very short, after his death the disciples continued to spread his teachings. Christianity has always found followers.

Coliseum

In the 1st and 2nd centuries AD e. Gladiator fights were very popular, and almost every Roman city had an arena or amphitheater. In 72 AD. Emperor Vespasian began construction of the Colosseum in the park of Nero's Golden House (Palace of Domus Aurea). Built in eight years, the amphitheater could accommodate up to 800,000 spectators. Animals and people who performed on stage were kept in underground corridors. The opening games lasted 100 days and nights, during which time 5,000 animals were killed. Gladiators were usually prisoners or slaves condemned to fight to the death. The Colosseum was both a political and sports arena. The exotic animals and foreign peoples displayed there in the center of Rome demonstrated the power and scale of the Empire.

Roman army

The legion commander (legate) was assisted by six tribunes, who gave orders to individual units of the army in battle. The legate, like the tribunes, was a candidate for a seat in the Senate. By the beginning of the Second Punic War, Rome had the greatest army. To the 32,000 infantry and cavalry of 1,600 horsemen, the Allied troops of 30,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry were added. Legions, armed, among other things, with spears, bows and short swords, together with Kaleriyot units, formed an effective combat-ready army. A well-organized command structure allowed for unexpected tactical maneuvers to destroy the enemy.

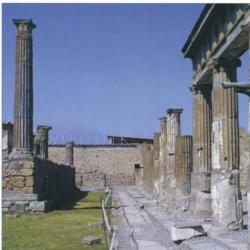

Temple of Apollo in Pompeii. Only in 1748, during excavations, a long-forgotten city buried under ashes was discovered.

Pompeii

The city of Pompeii on the west coast of Italy from 83 BC. e. was a Roman colony. Like neighboring Herculaneum, Pompeii was a wealthy city by average standards in the Roman Empire. In 63 AD e. Pompeii was shaken by an earthquake. It took ten years to rebuild the numerous destroyed villas and temples. August 27, 79 AD e. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius, located in the northern part of the city, began. Pliny the Elder witnessed this and subsequently spoke about what he saw in letters to the historiographer Tacitus. He described the earthquake that preceded the volcanic eruption, a giant column of smoke and a rain of ash particles from pyroclast rock. More than 2,000 people died when Pompeii was covered in a layer of hot ash and pumice 3 meters thick. Located southeast of Vesuvius, Herculaneum was covered with volcanic ash. The city was abandoned and forgotten until the 18th century, when its ruins were discovered.

Barbarians

Initially, the Romans and Greeks called all peoples who spoke non-Greek barbarians. Like the Greeks, the Romans considered barbarians uneducated, uncultured, and uncivilized. As the Roman Empire expanded, resistance intensified on the outer borders of the empire. Especially on the borders of the Rhine and Danube, unrest constantly arose, during which Roman fortifications were attacked. In some areas, Roman citizenship was granted to defeated peoples, so that men could serve in the Roman army. Thus, in some regions the Roman army underwent “Germanization”: on the one hand, while promoting the spread of Roman culture, the army at the same time persistently mixed with enemy tribes.

In intensive contact with Roman civilization, groups of non-Roman populations adopted Roman traditions and customs, and the local culture was increasingly displaced. At the same time, more and more regions gained autonomy, small independent states emerged, as, for example, in Gaul, they gained strength, which they could oppose to the collapsing Roman power.

Fall of Rome

The collapse of the Roman Empire continued for several centuries and had various causes. As the empire expanded, it became increasingly difficult to control the state. In the outlying provinces, many Roman soldiers and citizens adopted local customs. Numerous soldiers were more attracted to the peaceful life of a landowner than to military service. Attacks and invasions contributed to the weakening of the empire, and small tribes gathered into powerful alliances. The Goths united under a common command and in 378 AD. in the Battle of Adrianople they defeated the army of Flavius Valens and since then have become invincible for the Romans.

The large-scale expansion of the empire's borders at the end of the 3rd century under Emperor Diocletian led to the decentralization of government. The empire was divided into four administrative territories, ruled by tetrarchs. From within, the state was shaken by a series of civil wars. Individual armies of commanders realized that they were first of all obliged to their commanders, and only then to Rome. Some generals used their troops in competition for the imperial throne. Political intrigues led to the rapid rise and fall of emperors, as well as instability in government.

Under these conditions, Christianity gained more and more new supporters. In 313 AD. Allied emperors Constantine and Licinius issued an edict of tolerance towards Christians, in which they were granted freedom of religion and equal rights with everyone. In 323 AD, after defeating Licinius, Constantine began to lay claim to the entire empire. Seven years later, he moved the capital from Rome to Byzantium, to the east, and gave it the name Constantinople. Once a powerful city, Rome was now barely protected from raids and in 410 AD. was taken by the Visigoths and destroyed many times. Deposition of Emperor Romulus Augustus by the Germanic general Odoacer in 476 AD. sealed the end of the Western Roman Empire. From the Eastern Roman Empire the Byzantine Empire was formed, which lasted until 1453.

Above: Bust found in one of the Roman baths in Herculaneum, neighboring Pompeii, which was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. e.

106 A.D.

We are now entering the Christian era and can henceforth not mention “before” and “after” the Nativity of Christ, as we have done until now, in order to avoid confusion.

In 106 the emperor Trajan conquered Dacia. This country roughly corresponds to modern Romania. It was located north of the Danube - the border of the empire - and included the Carpathian mountain range.

The bas-reliefs of Trajan's Column in Rome depict the main episodes of this victorious campaign.

New province of Dacia will be partially colonized by settlers from all parts of the empire, they will take Latin as their language of communication, and it will give rise to Romanian language- the only Latin-based language of the eastern half of the empire. And this despite the fact that Greek culture predominated here.

Critical date

Why did we choose this date?

In the first century AD, the emperors continued the aggressive policy of the Republic, although not on such a scale as before.

Augustus captured Egypt, completed the conquest of Spain, and subdued the rebellious populations of the Alps, making the Danube the frontier of the empire.

To protect Gaul from barbarian invasions, he planned to conquer Germany, the territory between the Rhine and Elbe. At first he succeeds thanks to the defeat of his sons-in-law Drusus and Tiberius.

However, in 9 AD, the Germans rebelled under the leadership of Arminius (Hermann) and destroyed the legions of the legate Varus in the Teutoburg Forest. This catastrophe greatly agitated Augustus (they say that he cried, repeating: "Var, give me back my legions"), forced him, like his heirs, to refuse to move the border along the Rhine. For more than two centuries, the Rhine and Danube (linked in the upper reaches between Mainz and Rotisbon by a fortified wall) formed the border of the empire in continental Europe. In 43, Emperor Claudius annexed Britannia (modern England), which became a Roman province.

The conquest of Dacia in 106 was the last major territorial acquisition of the Roman emperors. After this date, the boundaries remained unchanged for more than a century.

Roman world

The first two centuries of the empire, corresponding approximately to the first two centuries of our era, were a period of internal peace and prosperity.

Limes- systems of border fortifications, along which legions stood, ensured security, which made it possible to develop trade relations and the economy.

New cities are built and developed according to the model of Rome: they have an autonomous administration with a Senate and elected magistrates. But in reality, as in Rome, power belongs to the rich, not without certain responsibilities on their part. Thus, they must, at their own expense, build water pipelines, public buildings: temples, baths, circuses or theaters, and also pay for circus performances.

This roman world cannot be idealized; brutally exploited provinces often rebel. We saw this in Judea. But these uprisings are constantly suppressed by the Roman army.

While wealth and slaves flocked to Rome through conquest or forays on the borders, a certain economic and social balance was maintained.

When the conquests stopped and attacks by “barbarians” (those who lived outside the empire) on Roman lands became more frequent An economic and social crisis is unfolding.

The “middle class” is supplying fewer and fewer citizen soldiers, so the Roman army is increasingly replenished with mercenaries, often these are barbarian immigrants who receive Roman citizenship or a piece of land at the end of their service.

After the reign of Augustus, imperial power became a stake in the struggle of rival armies located on various frontiers (on the Rhine, Danube and in the East), all too often called upon to march on Rome in order to install their commander on the throne. Due to these internal turmoil the borders are often left defenseless and subject to attacks by barbarians.

Crisis of the 3rd century

Difficulties begin during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180), a philosopher-emperor who expounds a humanistic philosophy in his Pensées. The peace-loving emperor is forced to spend most of his time repelling attacks on the borders of the state.

After his death, attacks from outside and internal unrest become more frequent.

In the 3rd century. begins a period called Late Empire.

The edict of Emperor Caracalla (212), according to which all free inhabitants of the empire received Roman citizenship, becomes the starting point in the evolution of the gradual merging of the “provincials” and the Romans.

Between 224 and 228 The Parthian Empire fell under the blows of the Sassanids, the founders of the new dynasty of the Persian Empire. This state would become a dangerous enemy for the Romans - Emperor Valerian would be captured by the Persians in 260 and die in captivity.

At the same time, due to internal rebellions and political instability (from 235 to 284, i.e. in 49 years, there were 22 emperors) barbarians penetrate the empire for the first time.

In 238 goths, Germanic tribe, first crossed the Danube and invaded the Roman provinces of Moesia and Thrace. From 254 to 259 another Germanic tribe, Alemanni, penetrates into Gaul, then into Italy and reaches the gates of Milan. Previously open, Roman cities build protective walls, including Rome, where Emperor Aurelian begins in 271 the construction of a fortress wall, the first after the one that once existed in the Rome of the kings.

The economic crisis manifests itself in a monetary crisis: due to a shortage of silver Emperors mint coins of low standard, in which the noble metal content is sharply reduced. As the value of such money falls, it happens price inflation.

Diocletian(284–305) tries to save the empire by reorganizing it. Considering that one person cannot ensure the defense of all borders, he divides the empire into four parts: in Milan and Nicomedia two emperors and their two assistants - “Caesars” appear, they are the deputies and heirs of the emperors.

End of the Roman Empire

In 326 the emperor Konstantin moves to Byzantium, a Greek city that controls the Bosphorus Strait, which connects the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. He gives this city his name, baptizing Constantinople(the city of Constantine), and makes it a “second Rome”.

In 395 the Roman Empire was finally divided into Western Roman Empire which will disappear in 476 under the blows of the barbarians, and Eastern Roman Empire, which will exist for another thousand years (until the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453). However, the latter will very soon become a country of Greek culture, and it will begin to be called the Byzantine Empire.

If you follow strictly the numbers and count the events from the time of Julius Caesar until the invasion of the Eternal City of the Visigoths under the leadership of Alaric I, then the Roman Empire lasted just under five centuries. And these centuries had such a powerful impact on the consciousness of the peoples of Europe that the phantom of empire still excites everyone’s imagination. Many works are devoted to the history of this state, in which a variety of versions of its “great fall” are expressed. True, if you put them into one picture, there is no fall as such. More like rebirth.

On August 24, 410, a group of rebellious slaves opened the Salt Gates of Rome to the Goths under the leadership of Alaric. For the first time in 800 years - since the day when the Senon Gauls of King Brennus besieged the Capitol - the Eternal City saw an enemy within its walls.

A little earlier, that same summer, the authorities tried to save the capital by presenting the enemy with three thousand pounds of gold (to “get” them, they had to melt down the statue of the goddess of valor and virtue), as well as silver, silk, leather, and Arabian pepper. As you can see, a lot has changed since the time of Brennus, to whom the townspeople proudly declared that Rome was being redeemed not with gold, but with iron. But here even gold did not save: Alaric reasoned that by capturing the city he would receive much more.

For three days his soldiers plundered the former “center of the world.” Emperor Honorius took refuge behind the walls of the well-fortified Ravenna, and his troops did not rush to the aid of the Romans. The best commander of the state, Flavius Stilicho (a Vandal by birth), was executed two years earlier on suspicion of conspiracy, and now there was practically no one to send against Alaric. And the Goths, having received their enormous booty, simply left unhindered.

Who is guilty?

“Tears flow from my eyes when I dictate...” confessed a few years later from the monastery in Bethlehem, Saint Jerome, the translator of the Holy Scriptures into Latin. He was echoed by dozens of lesser writers. Less than 20 years before Alaric’s invasion, the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, speaking about current military-political affairs, was still encouraging: “Ignorant people... say that such a hopeless darkness of disaster has never fallen on the state; but they are mistaken, struck by the horror of recently experienced misfortunes.” Alas, he was the one who was wrong.

The Romans immediately rushed to look for reasons, explanations and culprits. The population of the humiliated empire, already mostly Christianized, could not help but wonder: did the city fall because it turned away from the gods of their fathers? After all, back in 384, Aurelius Symmachus, the last leader of the pagan opposition, called on Emperor Valentinian II - return the altar of Victory to the Senate!

The opposite point of view was held by the Bishop of Hippo in Africa (now Annaba in Algeria), Augustine, later nicknamed the Blessed. “Did you believe,” he asked his contemporaries, “Ammianus when he said: Rome is “destined to live as long as humanity exists”? Do you think the world is ending now? Not at all! After all, the dominance of Rome in the Earthly City, unlike the City of God, cannot last forever. The Romans won world domination with their valor, but it was inspired by the search for mortal glory, and its fruits therefore turned out to be transitory. But the adoption of Christianity, recalls Augustine, saved many from the fury of Alaric. And indeed, the Goths, also already baptized, spared everyone who took refuge in the churches and at the relics of the martyrs in the catacombs.

Be that as it may, in those years Rome was no longer the magnificent and impregnable capital that the grandfathers of the citizens of the 5th century remembered. Increasingly, even emperors chose other large cities as their residence. And the Eternal City itself suffered a sad fate - over the next 60 years, desolate Rome was ravaged by barbarians twice more, and in the summer of 476 a significant event occurred. Odoacer, a German commander in Roman service, dethroned the last monarch, the young Romulus Augustus, who was mockingly nicknamed Augustulus (“Augusten”) after being overthrown. How can you not believe the irony of fate - only two ancient rulers of Rome were called Romulus: the first and the last. The state regalia were carefully preserved and sent to Constantinople, the eastern emperor Zeno. So the Western Roman Empire ceased to exist, and the Eastern one would last for another 1000 years - until the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453.

Why this happened - historians still do not stop judging and dressing up, and this is not surprising. After all, we are talking about a model empire in our retrospective imagination. After all, the term itself came to modern Romance languages (and even Russian) from its mother Latin. In most of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, traces of Roman rule remained - roads, fortifications, aqueducts. Classical education, based on ancient tradition, continues to be at the center of Western culture. The language of the vanished empire served as the international language of diplomacy, science, medicine until the 16th-18th centuries, and until the 1960s it was the language of Catholic worship. Without Roman law, jurisprudence is unthinkable in the 21st century.

How did it happen that such a civilization collapsed under the blows of the barbarians? Hundreds of works have been devoted to this fundamental issue. Experts have discovered many factors of decline: from the growth of bureaucracy and taxes to climate change in the Mediterranean basin, from the conflict between city and countryside to the smallpox pandemic... German historian Alexander Demandt counts 210 versions. Let's try to figure it out too.

|

|

Flavius Romulus Augustus(461 (or 463) - after 511), often called Augustulus, nominally ruled the Roman Empire from October 31, 475 to September 4, 476. The son of the influential army officer Flavius Orestes, who in the 70s of the 5th century rebelled against Emperor Julius Nepos in Ravenna and soon achieved success, placing his young son on the throne. However, the rebellion was soon suppressed by the commander Odoacer on behalf of the same Nepos, and the unlucky young man was deposed. However, contrary to cruel traditions, the authorities preserved his life, his estate in Campania and the state salary, which he received until his old age, including from the new ruler of Italy, the Goth Theodoric. |

|

Charles, nicknamed the Great during his lifetime (747-814), ruled the Franks from 768, the Lombards from 774, and the Bavarians from 778. In 800 he was officially declared Roman emperor (princeps). The path to the heights of success of the man from whose name, by the way, the word “king” in Slavic languages came from, was long: he spent his youth under the “wing” of his father Pepin the Short, then fought for dominance in Western Europe with his brother Carloman, but gradually with every year he increased his influence until he finally turned into that powerful ruler of the lands from the Vistula to the Ebro and from Saxony to Italy, the gray-bearded and wise judge of the peoples, whom historical legend knows. In 800, having supported Pope Leo III in Rome, whom his fellow countrymen were about to depose, he received from him a crown with which he was crowned with the words: “Long live and conquer Charles Augustus, the great and peace-making Roman Emperor crowned by God.” |

|

Otto I, also called Great by his contemporaries (912-973), Duke of Saxony, King of the Italians and East Franks, Holy Roman Emperor from 962. He strengthened his power in Central Europe, Italy, and eventually repeated the “option” of Charlemagne, only in a qualitatively new spirit - it was under him that the term “Holy Roman Empire” came into official political use. In Rome, after a solemn meeting, the pope presented him with a new imperial crown in the Church of St. Peter, and the emperor promised to return the former church possessions of the popes. |

|

Franz Joseph Karl von Habsburg(1768-1835), Emperor Franz II of Austria (1804-1835) and the last Holy Roman Emperor (1792-1806). A man who remains in history only as a kind family man and an implacable persecutor of revolutionaries is known mainly for the fact that he reigned during the era of Napoleon, hated him, and fought with him. After the next defeat of the Austrians by Napoleonic troops, the Holy Roman Empire was abolished - this time forever, unless, of course, we consider the current European Union (which, by the way, began with a treaty signed in 1957 in Rome) as a unique form of the Roman power. |

Anatomy of decline

By the 5th century, apparently, living in an empire that stretched from Gibraltar to the Crimea had become noticeably more difficult. The decline of cities is especially noticeable to archaeologists. For example, in the 3rd-4th centuries, about a million people lived in Rome (centers with such a large number of inhabitants did not appear in Europe until the 1700s). But soon the city's population declines sharply. How is this known? From time to time, the townspeople were given bread, olive oil and pork at state expense, and from the surviving registers with the exact number of recipients, historians have calculated when the decline began. So: 367 - there were about 1,000,000 Romans, 452 - there were 400,000 of them, after Justinian’s war with the Goths - less than 300,000, in the 10th century - 30,000. A similar picture can be seen in all the western provinces of the empire. It has long been noted that the walls of medieval cities that grew up on the site of ancient ones cover only about a third of the former territory. The immediate causes lie on the surface. For example: barbarians invade and settle on imperial lands, cities now have to be constantly defended - the shorter the walls, the easier it is to defend. Or - barbarians invade and settle on imperial lands, trade becomes increasingly difficult, large cities lack food. What's the solution? Former townspeople, of necessity, become farmers, and behind the fortress walls they only hide from endless raids.

Well, where cities decline, crafts also decline. Disappearing from everyday life - which is noticeable during excavations - is high-quality ceramics, which during the Roman heyday was literally produced on an industrial scale and was widespread in villages. The pots that peasants use during the period of decline cannot be compared with it; they are sculpted by hand. In many provinces, the potter's wheel has been forgotten, and will not be remembered for another 300 years! The production of tiles has almost ceased - roofs made of this material are replaced by easily rotting planks. How much less ore is mined and metal products are smelted is known from the analysis of traces of lead in Greenland ice (it is known that the glacier absorbs human waste products for thousands of kilometers around), carried out in the 1990s by French scientists: the level of sediments contemporary with early Rome remains unsurpassed until the Industrial Revolution at the beginning of modern times. And the end of the 5th century - at the prehistoric level... Silver coins continue to be minted for some time, but there is clearly not enough of it, Byzantine and Arab gold money is becoming more and more common, and small copper pennies are completely disappearing from circulation. This means that buying and selling has disappeared from the life of the common man. There is nothing else to trade regularly and there is no reason to.

True, it is worth noting that simply changes in material culture are often taken as signs of decline. A typical example: in Antiquity, grain, oil, and other bulk and liquid products were always transported in huge amphorae. A lot of them have been found by archaeologists: in Rome, fragments of 58 million discarded vessels made up the entire Monte Testaccio (“Pot Mountain”). They are perfectly preserved in water - they are usually used to find sunken ancient ships at the bottom of the sea. The marks on the amphorae traced all the routes of Roman trade. But from the 3rd century, large clay vessels are gradually replaced by barrels, of which, naturally, almost no traces remain - it’s good if somewhere you can identify an iron rim. It is clear that it is much more difficult to estimate the volume of such new trade than the old one. It’s the same with wooden houses: in most cases, only their foundations are found, and it is impossible to understand what once stood here: a miserable shack or a mighty building?

Are these reservations serious? Quite. Are they enough to doubt the decline as such? Still no. The political events of that time make it clear that it happened, but it is not clear how and when it began? Was it a consequence of defeats from the barbarians or, conversely, the cause of these defeats?

“The number of parasites is growing”

To this day, economic theory enjoys success in science: the decline began when, at the end of the 3rd century, taxes “suddenly” increased sharply. If initially the Roman Empire was actually a “state without bureaucracy” even by ancient standards (a country with a population of 60 million people kept only a few hundred officials on payroll) and allowed for broad local self-government, now, with an expanded economy, it became necessary to “strengthen the vertical authorities". There are already 25,000-30,000 officials in the service of the empire.

In addition, almost all monarchs, starting with Constantine the Great, spend funds from the treasury on the Christian church - priests and monks are exempt from taxes. And to the residents of Rome, who received free food from the authorities (for votes in elections or simply so as not to rebel), are added the residents of Constantinople. “The number of parasites is growing,” English historian Arnold Jones writes caustically about these times.

It is logical to assume that the tax burden has increased unsustainably as a result. In fact, the texts of that time are full of complaints about large taxes, and imperial decrees, on the contrary, are full of threats to non-payers. This is especially true for curials - members of municipal councils. They were responsible for making payments from their cities with their personal property and, naturally, constantly tried to evade the burdensome duty. Sometimes they even fled for their lives, and the central government, in turn, threateningly forbade them to leave their positions even for the sake of joining the army, which was always considered a holy cause for a Roman citizen.

All these constructions are obviously quite convincing. Of course, people have been complaining about taxes since they appeared, but in late Rome this indignation was much louder than in early Rome, and for good reason. True, charity, which spread along with Christianity, provided some outlet for charity (helping the poor, shelters at churches and monasteries), but in those days it had not yet managed to go beyond the walls of cities.

In addition, there is evidence that in the 4th century it was difficult to find soldiers for a growing army, even when the fatherland was seriously threatened. And many combat units, in turn, had to engage in farming using the artillery method in places of long-term deployment - the authorities no longer fed them. Well, since the legionnaires are plowing, and the rear rats are not going to serve, what can the residents of the border provinces do? Naturally, they spontaneously arm themselves, without “registering” their troops with the imperial authorities, and they themselves begin to guard the border along its entire huge perimeter. As the American scientist Ramsey McMullen aptly noted: “The inhabitants became soldiers, and the soldiers became ordinary people.” It is logical that the official authorities could not rely on the anarchist self-defense units. That is why barbarians begin to be invited into the empire - first as individual mercenaries, then as whole tribes. This worried many people. Bishop Sinesius of Cyrene, in his speech “On the Kingdom,” stated: “We hired wolves instead of watchdogs.” But it was too late, and although many barbarians served faithfully and brought Rome much benefit, it all ended in disaster. Approximately according to the following scenario. In 375, Emperor Valens allowed the Goths, who were retreating west under the onslaught of the Hunnic hordes, to cross the Danube and settle on Roman territory. Soon, due to the greed of the officials responsible for supplying food, famine begins among the barbarians, and they rebel. In 378, the Roman army was completely defeated by them at Adrianople (now Edirne in European Turkey). Valens himself fell in battle.

Similar stories of a smaller scale occurred in abundance. In addition, the poor citizens of the empire itself began to show increasing dissatisfaction: what kind of homeland is this, which not only stifles with taxes, but also invites its own destroyers to itself. People who were richer and more cultured, of course, remained patriots longer. And detachments of the rebellious poor - the Bagaudae (“militant”) in Gaul, the Scamari (“shippers”) in the Danube region, the Bucoli (“shepherds”) in Egypt — easily entered into alliances with the barbarians against the authorities. Even those who did not rebel openly behaved passively during invasions and did not offer much resistance if they were promised not to be plundered too much.

|

The main currency throughout most of imperial history was the denarius, first issued in the 3rd century BC. e. Its denomination was equal to 10 (later 16) smaller coins - asses. At first, even under the Republic, denarii were minted from 4 grams of silver, then the precious metal content dropped to 3.5 grams, under Nero they began to be produced in an alloy with copper, and in the 3rd century inflation reached such enormous proportions that this money was completely lost meaning to release. |

|

In the Eastern Roman Empire, which far outlived the Western and used Greek more often than Latin in official language, money was naturally called Greek. The basic unit of calculation was the liter, which, depending on the sample and metal, was equal to 72 (gold liters), 96 (silver) or 128 (copper) drachmas. At the same time, the purity of all these metals in the coin, as usual, decreased over time. There were also old Roman solidi in circulation, which are usually called nomisms, or bezants, or, in Slavic, zlatnitsa, and silver miliarisia, constituting one thousandth of a liter. All of them were minted before the 13th century, and were in use even later. |

|

The Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, and especially its era when Maria Theresa ruled, was most famous in monetary terms for the thaler. They are still famous, they are popular with numismatists, and in some places in Africa they are said to be used by shamans. This large silver coin, minted between the 16th and 19th centuries, was approved by the special Esslingen Imperial Coin Regulations in 1524 according to the standard of 27.41 grams of pure precious metal. (By the way, the name of the dollar in English comes from it - this is the continuity of empires in history.) Soon the new financial unit took a leading place in international trade. In Rus' they were called efimki. Moreover, money of the same standard was widely used: ecus and piastres - only variants and modifications of the thaler. It itself existed in Germany until the 1930s, when the three-mark coin was still called the thaler. Thus, he long outlived the empire that gave birth to him. |

Unfortunate coincidences

But why did the empire suddenly find itself in such a position that it had to take unpopular measures - invite mercenaries, raise taxes, inflate the bureaucracy? After all, for the first two centuries AD, Rome successfully held a vast territory and even captured new lands without resorting to the help of foreigners. Why was it necessary to suddenly divide the power between co-rulers and build a new capital on the Bosporus? Something went wrong? And why, again, did the eastern half of the state, unlike the western, survive? After all, the invasion of the Goths began precisely in the Byzantine Balkans. Here, some historians see an explanation in pure geography - the barbarians were unable to overcome the Bosporus and penetrate into Asia Minor, so vast and unravaged lands remained in the rear of Constantinople. But it can be argued that the same Vandals, heading to North Africa, for some reason easily crossed the wider Gibraltar.

In general, as the famous historian of Antiquity Mikhail Rostovtsev said, great events do not happen because of one thing, they always mix demography, culture, strategy...

Here are just a few points of such disastrous contacts for the Roman Empire, in addition to those already discussed above.

First, the empire did appear to have suffered from a massive smallpox epidemic at the end of the 2nd century, which, according to conservative estimates, reduced the population by 7-10%. Meanwhile, the Germans north of the border were experiencing a baby boom.

Secondly, in the 3rd century, gold and silver mines in Spain dried up, and the state lost new ones, Dacian (Romanian), by 270. Apparently, there are no more significant deposits of precious metals left at his disposal. But it was necessary to mint coins in huge quantities. In this regard, it remains a mystery how Constantine the Great (312-337) managed to restore the solidus standard, and how the emperor’s successors managed to keep the solidus very stable: the gold content in it did not decrease in Byzantium until 1070. The English scientist Timothy Garrard put forward a witty guess: perhaps in the 4th century the Romans received the yellow metal along the caravan routes from trans-Saharan Africa (however, the chemical analysis of the solids that have come down to us does not yet confirm this hypothesis). Nevertheless, inflation in the state is becoming more and more monstrous, and it is impossible to cope with it.

It also fails because the government turned out to be psychologically unprepared for the challenges of the time. Neighbors and foreign subjects had changed their fighting tactics and way of life quite a lot since the founding of the empire, and upbringing and education taught governors and generals to look for management models in the past. It was at this time that Flavius Vegetius wrote a characteristic treatise on military affairs: all troubles, he thinks, can be dealt with by restoring the classical legion of the era of Augustus and Trajan. Obviously this was a fallacy.

Finally - and this is perhaps the most important reason - the pressure on the empire from outside objectively intensified. The military organization of the state, created under Octavian at the turn of the era, could not cope with a simultaneous war on many borders. For a long time, the empire was simply lucky, but already under Marcus Aurelius (161-180) fighting took place simultaneously in many theaters ranging from the Euphrates to the Danube. The state's resources were under terrible strain - the emperor was forced to sell even his personal jewelry to finance the troops. If in the 1st-2nd centuries, on the most open border - the eastern - Rome was opposed by Parthia, which was no longer so powerful at that time, then from the beginning of the 3rd century it was replaced by the young and aggressive Persian kingdom of the Sassanids. In 626, shortly before this power itself fell under the blows of the Arabs, the Persians still managed to approach Constantinople itself, and Emperor Heraclius drove them away literally by a miracle (it was in honor of this miracle that an akathist to the Most Holy Theotokos was composed - “The Chosen Governor ...") . And in Europe, in the last period of Rome, the onslaught of the Huns, moving west along the Great Steppe, set in motion the entire process of the Great Migration of Peoples.

Over many centuries of conflicts and trade with the carriers of a high civilization, the barbarians learned a lot from them. Prohibitions on the sale of Roman weapons to them and training them in maritime affairs appear in the laws too late, in the 5th century, when they no longer have any practical meaning.

The list of factors can be continued. But on the whole, Rome apparently did not have a chance to resist, although no one will probably ever answer this question with precision. As for the different destinies of the Western and Eastern empires, the East was initially richer and more powerful economically. About the old Roman province of Asia (the “left” part of Asia Minor) they said that it had 500 cities. In the West, such indicators were not available anywhere except Italy itself. Accordingly, large rural owners occupied a stronger position here, extracting tax benefits for themselves and their tenants. The burden of taxes and administration fell on the shoulders of city councils, and the nobility spent their leisure time on country estates. At critical moments, Western emperors lacked both men and money. The Constantinople authorities have never faced such a threat. They had so many resources that they were even enough to launch a counteroffensive.

Together again?

Indeed, it was not long before much of the West returned to the direct rule of the emperors. Under Justinian (527-565), Italy with Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, Dalmatia, the entire coast of North Africa, southern Spain (including Cartagena and Cordoba), and the Balearic Islands were conquered. Only the Franks did not cede any territories and even received Provence for maintaining neutrality.

In those years, the biographies of many Romans (Byzantines) could serve as a clear illustration of the newly triumphant unity. Here, for example, is the life of the military leader Peter Marcellinus Liberius, who conquered Spain for Justinian. He was born in Italy around 465 into a noble family. He began serving under Odoacer, but the Ostrogoth Theodoric retained him in their service - someone educated had to collect taxes and keep the treasury. Around 493, Liberius became prefect of Italy - the head of the civil administration of the entire peninsula - and in this position showed zealous care for the overthrown Romulus Augustulus and his mother. The son of the worthy prefect took the post of consul in Rome, and his father soon also received military command in Gaul, which the German leaders usually did not trust to the Latins. He was friends with the Bishop of Arelat, Saint Caesar, and founded a Catholic monastery in Rome, continuing to serve the Arian Theodoric. And after his death he went to Justinian on behalf of the new Ostrogothic king Theodohad (he had to convince the emperor that he had rightly overthrown and imprisoned his wife Amalasunta). In Constantinople, Liberius remained to serve the co-religionist emperor and first received control of Egypt, and then in 550 he recaptured Sicily. Finally, in 552, when the commander and politician was already over 80, he managed to see the triumph of his dream - the return of Rome under common imperial rule. Then, having conquered Southern Spain, the old man returned to Italy, where he died at the age of 90. He was buried in his native Arimin (Rimini) with the greatest honors - with eagles, lictors and timpani.

Gradually, Justinian's conquests were lost, but not immediately - part of Italy recognized the power of Constantinople even in the 12th century. Heraclius I, pressed in the east by the Persians and Avars in the 7th century, was still thinking about moving the capital to Carthage. And Constans II (630-668) spent the last years of his reign in Syracuse. He, by the way, turned out to be the first Roman emperor after Augustulus to personally visit Rome, where, however, he became famous only for tearing off gilded bronze from the roof of the Pantheon and sending it to Constantinople.

|

Ravenna rose to prominence at the late stage of the Western Roman Empire due to its very convenient geographical position for those times. Unlike the “shapeless” Rome that had grown over the centuries and spread far beyond the seven hills, this city was surrounded by swampy backwaters on all sides - only a specially constructed causeway, which could easily be destroyed in a moment of danger, led to the walls of the new capital. Emperor Honorius was the first to choose this former Etruscan settlement as his permanent place of residence in 402; at the same time, majestic Christian churches arose in the city in large numbers. It was in Ravenna that Romulus Augustulus was crowned and deposed by Odoacer. |

|

Constantinople, as its name clearly indicates, was founded by the greatest Roman statesman of the late empire, a kind of “sunset Augustus” and the establisher of Christianity as the state religion - Constantine the Great on the site of the ancient Bosphorus settlement of Byzantium. After the division of the empire into Western and Eastern, it turned out to be the center of the latter, which it remained until May 29, 1453, when the Turks burst into its streets. A characteristic detail: even under Ottoman rule, being the capital of the empire of the same name, the city formally retained its main name - Constantinople (in Turkish - Konstantininiyo). Only in 1930, by order of Kemal Atatürk, did it finally become Istanbul. |

|

Aachen, founded by Roman legionaries near a source of mineral water under Alexander Severus (222-235), “came” to the Roman capitals virtually by accident - Charlemagne settled there permanently. Accordingly, the city received great trade and craft privileges from the new ruler, its splendor, fame and size began to grow steadily. In the XII-XIII centuries, the population of the city reached 100,000 people - a rare case at that time. In 1306, Aachen, adorned with a powerful cathedral, finally received the status of a free city of the Holy Roman See, and until very late times congresses of imperial princes were held here. The gradual decline began only in the 16th century, when the procedure for the wedding of sovereigns began to take place in Frankfurt. |

|

Vein was never officially considered the capital of the Holy Roman Empire, however, since from the 16th century the imperial title, which was gradually depreciating even then, belonged almost invariably to the Austrian Habsburg dynasty, the status of the main center of Europe automatically passed to the city on the Danube. At the end of the last era, the Celtic camp of Vindobona was located here, which already in 15 BC was conquered by legionnaires and turned into an outpost of the Roman power in the north. The new fortified camp defended itself from the barbarians for a long time - until the 5th century, when the entire state around was already in flames and falling apart. In the Middle Ages, the Margraviate of Austria gradually formed around Vienna, then it was she who consolidated the empire, and it was there that its abolition was announced in 1806. |

So was there a fall?

So why is it that in school textbooks the year 476 ends the history of Antiquity and serves as the beginning of the Middle Ages? Did some kind of radical change occur at this moment? In general, no. Long before this, most of the imperial territory was occupied by “barbarian kingdoms,” the names of which often in one form or another still appear on the map of Europe: Frankish in the north of Gaul, Burgundy a little to the southeast, Visigoths on the Iberian Peninsula, Vandals in North Africa (from their short stay in Spain the name Andalusia remained) and, finally, in Northern Italy - the Ostrogoths. Only in some places, at the time of the formal collapse of the empire, the old patrician aristocracy was still in power: the former emperor Julius Nepos in Dalmatia, Syagrius in the same Gaul, Aurelius Ambrosius in Britain. Julius Nepos would remain emperor for his supporters until his death in 480, and Syagrius would soon be defeated by the Franks of Clovis. And the Ostrogoth Theodoric, who would unite Italy under his rule in 493, would behave as an equal partner of the Emperor of Constantinople and heir to the Western Roman Empire. Only when, in the 520s, Justinian needed a reason to conquer the Apennines, his secretary would pay attention to the 476th - the cornerstone of Byzantine propaganda would be that the Roman power in the West had collapsed and it was necessary to restore it.

So, it turns out that the empire did not fall? Is it not more correct, in agreement with many researchers (of whom Princeton professor Peter Brown enjoys the greatest authority today), to believe that she was simply reborn? After all, even the date of her death, if you look closely, is arbitrary. Odoacer, although born a barbarian, in his entire upbringing and worldview belonged to the Roman world and, by sending the imperial regalia to the East, symbolically restored the unity of the great country. And the commander’s contemporary, the historian Malchus from Philadelphia, confirms that the Senate of Rome continued to meet both under him and under Theodoric. The learned man even wrote to Constantinople that “there is no longer any need to divide the empire; one emperor will be enough for both its parts.” Let us recall that the division of the state into two almost equal halves occurred back in 395 due to military necessity, but it was not considered as the formation of two independent states. Laws were issued in the name of two emperors throughout the entire territory, and of the two consuls, whose names designated the year, one was elected on the Tiber, the other on the Bosporus.

So, did much change in August 476 for the city’s residents? Perhaps it became harder for them to live, but a psychological breakdown in their minds did not happen overnight. Even at the beginning of the 8th century in distant England, the Venerable Bede wrote that “as long as the Colosseum stands, Rome will stand, but when the Colosseum collapses and Rome falls, the end of the world will come”: therefore, for Bede, Rome has not yet fallen. It was all the easier for the inhabitants of the Eastern Empire to continue to consider themselves Romans - the self-name “Romea” survived even after the collapse of Byzantium and survived into the twentieth century. True, they spoke Greek here, but this has always been the case. And the kings in the West recognized the theoretical supremacy of Constantinople - just as before 476 they formally swore allegiance to Rome (more precisely, Ravenna). After all, most tribes did not seize land in the vast expanses of the empire by force, but once received it under an agreement for military service. A characteristic detail: few of the barbarian leaders decided to mint their own coins, and Syagrius in Soissons even did it on behalf of Zeno. Roman titles also remained honorable and desirable for the Germans: Clovis was very proud when, after a successful war with the Visigoths, he received the post of consul from Emperor Anastasius I. What can we say, if in these countries the status of a Roman citizen remained valid, and its holders had the right to live according to Roman law, and not according to new codes of laws like the famous Frankish “Salic truth”.

Finally, the most powerful institution of the era—the Church—lived in unity; the separation of Catholics and Orthodox after the era of the seven Ecumenical Councils was still far away. In the meantime, the primacy of honor was firmly recognized for the bishop of Rome, the vicar of St. Peter, and the papal office, in turn, dated its documents until the 9th century according to the years of the reign of the Byzantine monarchs. The old Latin aristocracy retained its influence and connections - although the new barbarian masters did not really trust it, but in the absence of others they had to take its enlightened representatives as advisers. Charlemagne, as you know, did not even know how to write his name. There is a lot of evidence of this: for example, just around 476, Sidonius Apollinaris, Bishop of Arverne (or Auvergne), was thrown into prison by the Visigothic king Eurich for calling on the cities of Auvergne not to betray direct Roman authority and resist the newcomers. And he was saved from captivity by Leon, a Latin writer, at that time one of the main dignitaries of the Visigothic court.

Regular communication within the collapsed empire, trade and private, also remained for the time being, only the Arab conquest of the Levant in the 7th century put an end to intensive Mediterranean trade.

Eternal Rome

When Byzantium, bogged down in wars with the Arabs, nevertheless lost control over the West... the Roman Empire was revived there again, like a phoenix! On Christmas Day 800, Pope Leo III placed her crown on the Frankish king Charlemagne, who united most of Europe under his rule. And although under Charles’s grandchildren this large state disintegrated again, the title was preserved and long outlived the Carolingian dynasty. The Holy Roman Empire of the German nation lasted until modern times, and many of its rulers, right up to Charles V of Habsburg in the 16th century, tried to unite the entire continent again. To explain the shift of the imperial “mission” from the Romans to the Germans, the concept of “transfer” (translatio imperii) was even specially created, which owes much to the ideas of Augustine: the power as a “kingdom that will never be destroyed” (the expression of the prophet Daniel) always remains, but peoples worthy of it change, as if taking over the baton from each other. The German emperors had grounds for such claims, so that formally they can be recognized as the heirs of Octavian Augustus - all the way up to the good-natured Francis II of Austria, who was forced to relinquish his ancient crown only by Napoleon after Austerlitz, in 1806. The same Bonaparte finally abolished the name itself, which had hovered over Europe for so long.

And the famous classifier of civilizations, Arnold Toynbee, generally proposed ending the history of Rome in 1970, when the prayer for the health of the emperor was finally excluded from Catholic liturgical books. But still, let's not go too far. The collapse of the power really turned out to be extended over time - as usually happens at the end of great eras - the very way of life and thoughts gradually and imperceptibly changed. In general, the empire died, but the promise of the ancient gods and Virgil is fulfilled - the Eternal City stands to this day. The past is perhaps more alive here than anywhere else in Europe. Moreover, he combined what remained of the classical Latin era with Christianity. The miracle did happen, as millions of pilgrims and tourists can testify. Rome is still the capital not only for Italy. So be it - history (or providence) always turns out to be wiser than people.

The Roman Empire (ancient Rome) left an imperishable mark on all European lands wherever its victorious legions set foot. The stone ligature of Roman architecture has been preserved to this day: walls that protected citizens, along which troops moved, aqueducts that delivered fresh water to citizens, and bridges thrown over stormy rivers. As if all this were not enough, the legionnaires erected more and more structures - even as the borders of the empire began to recede. During the era of Hadrian, when Rome was much more concerned with consolidating the lands than with new conquests, the unclaimed military prowess of soldiers, long separated from home and family, was wisely directed in another creative direction. In a sense, everything European owes its birth to the Roman builders who introduced many innovations both in Rome itself and beyond. The most important achievements of urban planning, which had the goal of public benefit, were sewerage and water supply systems, which created healthy living conditions and contributed to the increase in population and the growth of the cities themselves. But all this would have been impossible if the Romans had not invented concrete and did not begin to use the arch as the main architectural element. It was these two innovations that the Roman army spread throughout the empire.

Since stone arches could withstand enormous weight and could be built very high - sometimes two or three tiers - engineers working in the provinces easily crossed any rivers and gorges and reached the farthest edges, leaving behind strong bridges and powerful water pipelines (aqueducts). Like many other structures built with the help of Roman troops, the bridge in the Spanish city of Segovia, which carries a water supply, has gigantic dimensions: 27.5 m in height and about 823 m in length. Unusually tall and slender pillars, made of roughly hewn and unfastened granite blocks, and 128 graceful arches leave the impression of not only unprecedented power, but also imperial self-confidence. This is a miracle of engineering, built about 100 thousand years ago. e., has stood the test of time: until recently, the bridge served the water supply system of Segovia.

How it all began?

Early settlements on the site of the future city of Rome arose on the Apennine Peninsula, in the valley of the Tiber River, at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. e. According to legend, the Romans descend from Trojan refugees who founded the city of Alba Longa in Italy. Rome itself, according to legend, was founded by Romulus, the grandson of the king of Alba Longa, in 753 BC. e. As in the Greek city-states, in the early period of the history of Rome it was ruled by kings who enjoyed virtually the same power as the Greek ones. Under the tyrant king Tarquinius Proud, a popular uprising took place, during which the royal power was destroyed and Rome turned into an aristocratic republic. Its population was clearly divided into two groups - the privileged class of patricians and the class of plebeians, which had significantly fewer rights. A patrician was considered a member of the most ancient Roman family; only the senate (the main government body) was elected from the patricians. A significant part of its early history is the struggle of the plebeians to expand their rights and transform members of their class into full Roman citizens.

Ancient Rome differed from the Greek city-states because it was located in completely different geographical conditions - a single Apennine peninsula with vast plains. Therefore, from the earliest period of its history, its citizens were forced to compete and fight with neighboring Italic tribes. The conquered peoples submitted to this great empire either as allies, or were simply included in the republic, and the conquered population did not receive the rights of Roman citizens, often turning into slaves. The most powerful opponents of Rome in the 4th century. BC e. there were Etruscans and Samnites, as well as separate Greek colonies in southern Italy (Magna Graecia). And yet, despite the fact that the Romans were often at odds with the Greek colonists, the more developed Hellenic culture had a noticeable impact on the culture of the Romans. It got to the point that the ancient Roman deities began to be identified with their Greek counterparts: Jupiter with Zeus, Mars with Ares, Venus with Aphrodite, etc.

Wars of the Roman Empire

The most tense moment in the confrontation between the Romans and the southern Italians and Greeks was the war of 280-272. BC e., when Pyrrhus, the king of the state of Epirus, located in the Balkans, intervened in the course of hostilities. In the end, Pyrrhus and his allies were defeated, and by 265 BC. e. The Roman Republic united all of Central and Southern Italy under its rule.

Continuing the war with the Greek colonists, the Romans clashed with the Carthaginian (Punic) power in Sicily. In 265 BC. e. the so-called Punic Wars began, lasting until 146 BC. e., almost 120 years. Initially, the Romans fought against the Greek colonies in eastern Sicily, primarily against the largest of them, the city of Syracuse. Then the seizure of Carthaginian lands in the east of the island began, which led to the fact that the Carthaginians, who had a strong fleet, attacked the Romans. After the first defeats, the Romans managed to create their own fleet and defeat the Carthaginian ships in the battle of the Aegatian Islands. A peace was signed, according to which in 241 BC. e. all of Sicily, considered the breadbasket of the Western Mediterranean, became the property of the Roman Republic.

Carthaginian dissatisfaction with the results First Punic War, as well as the gradual penetration of the Romans into the territory of the Iberian Peninsula, which was owned by Carthage, led to a second military clash between the powers. In 219 BC. e. The Carthaginian commander Hannibal Barki captured the Spanish city of Saguntum, an ally of the Romans, then passed through southern Gaul and, having overcome the Alps, invaded the territory of the Roman Republic itself. Hannibal was supported by part of the Italian tribes who were dissatisfied with the rule of Rome. In 216 BC. e. in Apulia, in the bloody battle of Cannae, Hannibal surrounded and almost completely destroyed the Roman army, commanded by Gaius Terentius Varro and Aemilius Paulus. However, Hannibal was unable to take the heavily fortified city and was eventually forced to leave the Apennine Peninsula.

The war was moved to northern Africa, where Carthage and other Punic settlements were located. In 202 BC. e. The Roman commander Scipio defeated Hannibal's army near the town of Zama, south of Carthage, after which peace was signed on terms dictated by the Romans. The Carthaginians were deprived of all their possessions outside Africa and were obliged to transfer all warships and war elephants to the Romans. Having won the Second Punic War, the Roman Republic became the most powerful state in the Western Mediterranean. The Third Punic War, which took place from 149 to 146 BC. e., came down to finishing off an already defeated enemy. In the spring of 14b BC. e. Carthage was taken and destroyed, and its inhabitants.

Defensive walls of the Roman Empire

The relief from Trajan's Column depicts a scene (see left) from the Dacian Wars; Legionnaires (they are without helmets) are constructing a camp camp from rectangular pieces of turf. When Roman soldiers found themselves in enemy lands, the construction of such fortifications was common.

“Fear gave birth to beauty, and ancient Rome was miraculously transformed, changing its previous - peaceful - policy and began hastily erecting towers, so that soon all seven of its hills sparkled with the armor of a continuous wall.”- this is what one Roman wrote about the powerful fortifications built around Rome in 275 for protection against the Goths. Following the example of the capital, large cities throughout the Roman Empire, many of which had long since “stepped over” the boundaries of their former walls, hastened to strengthen their defensive lines.

The construction of the city walls was extremely labor-intensive work. Usually two deep ditches were dug around the settlement, and a high earthen rampart was piled between them. It served as a kind of layer between two concentric walls. External the wall went 9 m into the ground so that the enemy could not make a tunnel, and at the top it was equipped with a wide road for patrolmen. The inner wall rose a few more meters to make it more difficult to shell the city. Such fortifications were almost indestructible: their thickness reached 6 m, and the stone blocks were fitted to each other with metal brackets - for greater strength.

When the walls were completed, construction of the gates could begin. A temporary wooden arch - formwork - was built over the opening in the wall. On top of it, skilled masons, moving from both sides to the middle, laid wedge-shaped slabs, forming a bend in the arch. When the last - the castle, or key - stone was installed, the formwork was removed, and next to the first arch they began to build a second one. And so on until the entire passage to the city was under a semicircular roof - the Korobov vault.

The guard posts at the gates that guarded the peace of the city often looked like real small fortresses: there were military barracks, stocks of weapons and food. In Germany, the so-called one is perfectly preserved (see below). On its lower beams there were loopholes instead of windows, and on both sides there were round towers - to make it more convenient to fire at the enemy. During the siege, a powerful grate was lowered onto the gate.

The wall, built in the 3rd century around Rome (19 km long, 3.5 m thick and 18 m high), had 381 towers and 18 gates with lowering portcullis. The wall was constantly renewed and strengthened, so that it served the City until the 19th century, that is, until artillery was improved. Two thirds of this wall still stands today.

The majestic Porta Nigra (that is, the Black Gate), rising 30 m in height, personifies the power of imperial Rome. The fortified gate is flanked by two towers, one of which is significantly damaged. The gate once served as an entrance to the city walls of the 2nd century AD. e. to Augusta Trevirorum (later Trier), the northern capital of the empire.

Aqueducts of the Roman Empire. The road of life of the imperial city

The famous three-tier aqueduct in Southern France (see above), spanning the Gard River and its low-lying valley - the so-called Gard Bridge - is as beautiful as it is functional. This structure, stretching 244 m in length, supplies about 22 tons of water daily from a distance of 48 km to the city of Nemaus (now Nimes). The Garda Bridge still remains one of the most wonderful works of Roman engineering art.

For the Romans, famous for their achievements in engineering, the subject of special pride was aqueducts. They supplied ancient Rome with about 250 million gallons of fresh water every day. In 97 AD e. Sextus Julius Frontinus, superintendent of Rome’s water supply system, rhetorically asked: “Who dares to compare our water pipelines, these great structures without which human life is unthinkable, with the idle pyramids or some worthless - albeit famous - creations of the Greeks?” Towards the end of its greatness, the city acquired eleven aqueducts through which water ran from the southern and eastern hills. Engineering has turned into real art: it seemed that the graceful arches easily jumped over obstacles, besides decorating the landscape. The Romans quickly “shared” their achievements with the rest of the Roman Empire, and remnants can still be seen today numerous aqueducts in France, Spain, Greece, North Africa and Asia Minor.

To provide water to provincial cities, whose population had already exhausted local supplies, and to build baths and fountains there, Roman engineers laid canals to rivers and springs, often tens of miles away. Flowing at a slight slope (Vitruvius recommended a minimum slope of 1:200), the precious moisture ran through stone pipes that ran through the countryside (and were mostly hidden into underground tunnels or ditches that followed the contours of the landscape) and eventually reached the city limits. There, water flowed safely into public reservoirs. When the pipeline encountered rivers or gorges, the builders threw arches over them, allowing them to maintain the same gentle slope and maintain a continuous flow of water.

To ensure that the angle of incidence of water remained constant, surveyors again resorted to thunder and horobath, as well as a diopter that measured horizontal angles. Again, the main burden of work fell on the shoulders of the troops. In the middle of the 2nd century AD. one military engineer was asked to understand the difficulties encountered during the construction of the aqueduct in Salda (in present-day Algeria). Two groups of workers began to dig a tunnel in the hill, moving towards each other from opposite sides. The engineer soon realized what was going on. “I measured both tunnels,” he later wrote, “and found that the sum of their lengths exceeded the width of the hill.” The tunnels simply did not meet. He found a way out of the situation by drilling a well between the tunnels and connecting them, so that the water began to flow as it should. The city honored the engineer with a monument.

Internal situation of the Roman Empire

The further strengthening of the external power of the Roman Republic was simultaneously accompanied by a deep internal crisis. Such a significant territory could no longer be governed in the old way, that is, with the organization of power characteristic of a city-state. In the ranks of the Roman military leaders, commanders emerged who claimed to have full power, like the ancient Greek tyrants or the Hellenic rulers in the Middle East. The first of these rulers was Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who captured in 82 BC. e. Rome and became an absolute dictator. Sulla's enemies were mercilessly killed according to lists (proscriptions) prepared by the dictator himself. In 79 BC. e. Sulla voluntarily renounced power, but this could no longer return him to his previous control. A long period of civil wars began in the Roman Republic.

External situation of the Roman Empire

Meanwhile, the stable development of the empire was threatened not only by external enemies and ambitious politicians fighting for power. Periodically, slave uprisings broke out on the territory of the republic. The largest such rebellion was a rebellion led by the Thracian Spartacus, which lasted almost three years (from 73 to 71 BC). The rebels were defeated only by the combined efforts of the three most skilled commanders of Rome at that time - Marcus Licinius Crassus, Marcus Licinius Lucullus and Gnaeus Pompey.

Later, Pompey, famous for his victories in the East over the Armenians and the Pontic king Mithridates VI, entered into a battle for supreme power in the republic with another famous military leader, Gaius Julius Caesar. Caesar from 58 to 49 BC. e. managed to capture the territories of the northern neighbors of the Roman Republic, the Gauls, and even carried out the first invasion of the British Isles. In 49 BC. e. Caesar entered Rome, where he was declared a dictator - a military ruler with unlimited rights. In 46 BC. e. in the battle of Pharsalus (Greece) he defeated Pompey, his main rival. And in 45 BC. e. in Spain, under Munda, he crushed the last obvious political opponents - the sons of Pompey, Gnaeus the Younger and Sextus. At the same time, Caesar managed to enter into an alliance with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, effectively subordinating her huge country to power.

However, in 44 BC. e. Gaius Julius Caesar was killed by a group of Republican conspirators, led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Civil wars in the republic continued. Now their main participants were Caesar's closest associates - Mark Antony and Gaius Octavian. First, they destroyed Caesar’s killers together, and later they began to fight each other. Antony was supported by the Egyptian queen Cleopatra during this last stage of the civil wars in Rome. However, in 31 BC. e. In the Battle of Cape Actium, the fleet of Antony and Cleopatra was defeated by the ships of Octavian. The Queen of Egypt and her ally committed suicide, and Octavian, finally to the Roman Republic, became the unlimited ruler of a giant power that united almost the entire Mediterranean under his rule.

Octavian, in 27 BC. e. who took the name Augustus “blessed”, is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, although this title itself at that time meant only the supreme commander in chief who won a significant victory. Officially, no one abolished the Roman Republic, and Augustus preferred to be called princeps, that is, the first among senators. And yet, under Octavian’s successors, the republic began to more and more acquire the features of a monarchy, closer in its organization to the eastern despotic states.

The empire reached its highest foreign policy power under Emperor Trajan, who in 117 AD. e. conquered part of the lands of Rome's most powerful enemy in the east - the Parthian state. However, after the death of Trajan, the Parthians managed to return the captured territories and soon went on the offensive. Already under Trajan's successor, Emperor Hadrian, the empire was forced to switch to defensive tactics, building powerful defensive ramparts on its borders.

It was not only the Parthians who worried the Roman Empire; Incursions by barbarian tribes from the north and east became more and more frequent, in battles with which the Roman army often suffered severe defeats. Later, Roman emperors even allowed certain groups of barbarians to settle on the territory of the empire, provided that they guarded the borders from other hostile tribes.

In 284, the Roman Emperor Diocletian carried out an important reform that finally transformed the former Roman Republic into an imperial state. From now on, even the emperor began to be called differently - “dominus” (“lord”), and a complex ritual, borrowed from the eastern rulers, was introduced at court. At the same time, the empire was divided into two parts - Eastern and Western, at the head of each of which was a special ruler who received title of Augustus. He was assisted by a deputy called Caesar. After some time, Augustus had to transfer power to Caesar, and he himself would retire. This more flexible system, along with improvements in provincial government, meant that this great state continued to exist for another 200 years.

In the 4th century. Christianity became the dominant religion in the empire, which also contributed to strengthening the internal unity of the state. Since 394, Christianity is already the only permitted religion in the empire. However, if the Eastern Roman Empire remained a fairly strong state, the Western Empire weakened under the blows of the barbarians. Several times (410 and 455) barbarian tribes captured and ravaged Rome, and in 476 the leader of the German mercenaries, Odoacer, overthrew the last Western emperor, Romulus Augustulus, and declared himself ruler of Italy.